Altered States of Reading #6: Stories of Your (Future, Past) Life

Sunday, 27 November, 2016

Few films could better illustrate the workings of precognition than Denis Villeneuve’s excellent new film Arrival, based on a 1999 story “The Story of Your Life” by Ted Chiang. If you’ve seen the trailers, it will give nothing away that it is about a first-contact situation, and the attempt of a linguist, played by Amy Adams, to communicate with the visitors. It is only a slight spoiler to say that cracking the aliens’ code requires thinking differently about time. But do not read the rest of this post if you have not seen the film, as much depends on the twist ending that I am going to discuss.

Prophecy is a quiet, unconscious signal of reward on a noisy channel; you only really know it was prophecy, and see exactly how your actions had operated to fulfill it, after the fact.

The minor spoiler is that thinking in the aliens’ written language, “Heptapod B,” gives Amy Adams’ character an altered, precognitive vantage point. The big, very satisfying plot twist in Arrival rivals that in The Sixth Sense: The linguist’s realization about time reveals that what seems (at least to the viewer) like memories of her past are really visions of what is to come. That theme should be very familiar to readers of this blog.

One of the things Arrival gets right about prophecy is that it is not about events in some generalized future history, but about emotional upheavals, both major and minor, in our own future timeline. Future emotional experiences reflux backward and subtly inform our actions and our thoughts in the present. Adams’ character gets a crucial clue to her present situation from a vision of herself reading the book on Heptapod B that she is destined to write in her future. (In several of my posts I’ve described this “reading our own future writings” as a motor of creativity.) In the film’s climactic scene, she proves herself to the Chinese general by telling him his wife’s dying words, something she is able to do because he will remind her of this event, and of those words, months or years later at a gala in her honor. (This is the exact mechanism—producing information we will learn later—by which mediumship works, as I described in my recent post on that subject.)

However, linear human language is not the only (or even the main) thing standing in the way of accessing a broadened view of our own relation to time. For one thing, even if the future is set in stone, our awareness of it could only ever be oblique until events come to pass and it becomes clear in hindsight. Prophecy occurs in the future perfect tense: What we will have known, what will have turned out. It is an unconscious phenomenon.

My only slight quibble with Arrival is that, once Adams’ character understands that she is seeing her own future, that future remains too clear to her, and thus theoretically too open to her intervention. She chooses it anyway, despite knowing it will have a sad outcome, and thus no harm done from a paradox point of view. In Chiang’s “The Story of Your Life,” the parts of the story that lie in the narrator’s future are told in the simple future tense: She feels compelled to fulfill her knowledge of what will come, because with the altered mindset of thinking in Heptapod B, outcomes take on a new kind of psychological necessity; it is satisfying to fulfill them. But by the necessary logic of post-selection, it really wouldn’t—and in my experience doesn’t—work that way.* Prophecy is a quiet, unconscious signal of reward on a noisy channel; you only really know it was prophecy, and see exactly how your actions had operated to fulfill it, after the fact. Future perfect, in other words, not simple future.

My only slight quibble with Arrival is that, once Adams’ character understands that she is seeing her own future, that future remains too clear to her, and thus theoretically too open to her intervention. She chooses it anyway, despite knowing it will have a sad outcome, and thus no harm done from a paradox point of view. In Chiang’s “The Story of Your Life,” the parts of the story that lie in the narrator’s future are told in the simple future tense: She feels compelled to fulfill her knowledge of what will come, because with the altered mindset of thinking in Heptapod B, outcomes take on a new kind of psychological necessity; it is satisfying to fulfill them. But by the necessary logic of post-selection, it really wouldn’t—and in my experience doesn’t—work that way.* Prophecy is a quiet, unconscious signal of reward on a noisy channel; you only really know it was prophecy, and see exactly how your actions had operated to fulfill it, after the fact. Future perfect, in other words, not simple future.Whether we possess “free will” (and thus prophecy must remain an unconscious process because of that), or whether consciousness itself is an illusion, I don’t know. Those seem to some like the only philosophical options in a universe that includes retrocausation. I’m not so sure if that is the case, but I’m not that bothered by the problem: As a Zen-ist, I think both “free will” and “consciousness”—at least, as the terms are being used in the current culture scuffles around scientism and materialism (boo, hiss)—are MacGuffins. It doesn’t matter how we choose to talk (or write) about the human experience: Whether we say “the mind is material/based in the brain” or whether we say “it’s all consciousness,” doesn’t matter. Either way, we’re still here, the sun still rises in the morning, nothing has changed. Ceci n’est pas une pipe. No hay banda. It’s all a recording.

Simple Past Lives or Past Perfect Lives?

In an earlier installment I argued that supposed memories of past lives are more profitably thought of as prophecies of things we will learn in our future, using the fictional example of Max Ehrlich’s 1973 novel The Reincarnation of Peter Proud; the story works just as well, and indeed is just a tad more intellectually satisfying, thinking of it as a story about misrecognized precognition. (Phil Dick thought so too.)

Because precognition is so hard to think, the mind naturally grasps at the easier, linear-causal explanation: that a past life is being remembered in this one.

A vivid, real-life example susceptible to exactly such a reframing is police detective Robert L. Snow’s memoir of his own presumed past-life regression experience and his subsequent startling discovery of its meaning, Portrait of a Past Life Skeptic. At the start of the book, the past-life-curious Snow had read Coming Back by Raymond Moody, and while intrigued, was skeptical, given all he knew from his own work about the susceptibility of hypnosis subjects to false memory implantation.** But after a fortuitous encounter at a party with a therapist friend who told him her colleague conducted past-life regression in her practice, he accepted his friend’s dare to give the process a try and see for himself what he thought of it.

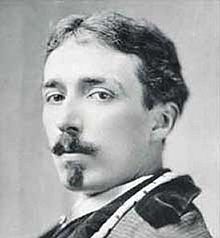

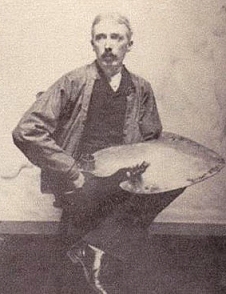

During the 45-minute, $60 session, which he tape recorded, Snow was stunned to find himself mentally transported back to the late 1800s, in the body of a painter, with vivid scenes of some of the art he had created, including a portrait of a woman with a hunchback. The vividness and “reality” of the experience was startling to him, and this compelled him to take the experiences seriously. He decided it should be a simple matter to scour art books at his local library and find the paintings he had seen, to gain verification that the experience was really based on cryptomnesia, artworks he had somehow seen and forgotten in his past. But weeks of investigation turned up nothing.

Then, a couple months later, Snow and his wife took a trip to New Orleans, where they idly visited some antique shops and art galleries. In the back of a small store, Snow was stunned to find the very portrait of the hunchback woman he had seen himself paint in his regression:

The gallery owner was able to tell Snow the name of the artist, James Carroll Beckwith, along with a bit of information about his life. Snow then made Beckwith a “case,” uncovering considerable more information that corroborated details remembered and recorded in his regression experience, including where and when Beckwith had lived and died, awards he had won, and his general attitude to his career.Whirling around, I stared open-mouthed at the portrait, reliving an experience I’d had once when I grabbed onto a live wire without knowing it, the current freezing me in my tracks as huge voltage surged up and down my arms and legs. Very similar to that experience, I simply stood frozen in the art gallery for what seemed like a long time, electricity racing up and down my arms as I stared at the portrait of the hunchbacked woman. …

Police officers don’t like to encounter startling coincidences, such as the finding of this painting, because we so very often find that these events are actually staged events made to look like coincidences. Yet I didn’t see how that could be the case in this situation.

On a visit to the Indianapolis Museum of Art to gather more information on the artist, Snow encountered a second painting he had also seen during his regression, and experienced the same electric sensation. At every turn, each new discovery eroded further his initial conviction that he had simply produced those memories from some past encounter with Beckwith’s art that he had forgotten. For instance, during his regression he had found himself arguing with someone about the bad lighting on one of his paintings in an exhibition. He then found, reading Beckwith’s diaries, nine separate incidents of the artist “having a row” over bad lighting or display of his pictures. There was no way that, as someone with no prior experience or knowledge of art, he could have known about Beckwith in this degree of detail.

On a visit to the Indianapolis Museum of Art to gather more information on the artist, Snow encountered a second painting he had also seen during his regression, and experienced the same electric sensation. At every turn, each new discovery eroded further his initial conviction that he had simply produced those memories from some past encounter with Beckwith’s art that he had forgotten. For instance, during his regression he had found himself arguing with someone about the bad lighting on one of his paintings in an exhibition. He then found, reading Beckwith’s diaries, nine separate incidents of the artist “having a row” over bad lighting or display of his pictures. There was no way that, as someone with no prior experience or knowledge of art, he could have known about Beckwith in this degree of detail. “It all fit,” Snow writes. “There was no one startling and gigantic fact, just one small confirmation after another.”

Thus the experience in the hypnotist’s office and the subsequent research project became for Snow much more than a case; it became something akin to a religious—or at least, metaphysical—conversion. Unable to imagine another explanation for the veridical nature of his “regression,” the detective braved potential ridicule and career hassles by writing and publishing a book on his experience as the basis for his newly-won conviction of the reality of past lives.

But even if it is less easy to wrap our heads around, there is another, even more parsimonious explanation for his experience, and it is precisely that of the plot twist in Arrival: All the information he assumed was a “memory” a previous existence over a century earlier was really information he would later discover or uncover in the course of a very exciting personal journey that was ahead of him in this lifetime. His book is a chronicle of these discoveries, and is perhaps even analogous to Amy Adams’ character’s future definitive study The Universal Language: Translating Heptapod B, which she consults in a key scene. Snow’s narrative, at every turn, is one of confirmation—of extracting and piecing together a “story latent in the landscape” he traversed. There were few details in his hypnosis session that were not confirmed in some way, which should to us be a tip-off that those confirmations were really possibly the source of his experiences during the hypnotic trance.

Prophetic Jouissance

Snow’s “confirmations” of material he had precognized were strikingly both unsettling and rewarding, the “jouissance” we see again and again with confirmations of psi experience. Unfortunately, because precognition is so hard to think, the mind naturally grasps at the easier, linear-causal explanation: that a past life is being remembered in this one. But we must not forget that that “past life” can only be confirmed in books and paintings and other sources of information the individual will encounter in the here and now—altered states of reading, yet again.

Misrecognized precognition could be a powerful, hitherto unexplored model of religious conversion and conviction.

What we need to assume as part of this is “time loops,” the crucial, paradoxical-seeming but in fact necessary PhilDickian nuance to the precognitive life. Snow might have encountered the hunchback portrait on his own, but he would not have done the subsequent research on Carroll had it not been for the regression experience that made the initial hunchback portrait encounter so uncanny. His research produced information that would pre-appear in that experience, and the journey was rewarding and thus precognized in a trance because of the unfolding excitement of solving a detective story … a detective story about a person he gradually came to believe was himself. As long as precognition is misrecognized as something else (e.g., “synchronicity” or “past lives”), and as long as it focuses on rewards, as I argue it always does even when it seems to be about “trauma,” then it will have a self-confirming tendency and thus not be paradoxical. No grandfathers harmed.

Some jolt toward personal growth is part of the excitement seen again and again in the most compelling synchronicity narratives, and it is the most basic kind of reward that precognition operates on. Carl Jung’s story of his patient’s precognitive dream about the scarab is, so to speak, the “archetypal” example. We are oriented toward exciting and validating discoveries in our future; the reward of a therapeutic insight or moment, suddenly feeling like a bigger, more complete and whole person, with greater self-knowledge—or what Jung called “individuation”—is a very powerful reward. This is why, as open-minded psychoanalysts like Jule Eisenbud noted, psi (as precognition) manifests so consistently in the therapeutic encounter; patients precognitively orient toward their own growth, not to mention pleasing their therapists by validating their theories.

In Snow’s case, already in the first chapter of his book we have a significant detail about why this particular figure of James Carroll Beckwith might have resonated so strongly, and thus been so rewarding to learn about over the course of his detective adventure.

In Snow’s case, already in the first chapter of his book we have a significant detail about why this particular figure of James Carroll Beckwith might have resonated so strongly, and thus been so rewarding to learn about over the course of his detective adventure. Snow, who is the author of several other books about police work, says he wanted to be a writer when he was young, and that he never had an aspiration to be a police officer. Yet life often has other plans for us, and his life took him down probably the most diametrically opposed path imaginable: into the military and then, because police work was a growth career at a time he needed a job, toward being a police detective.

The life of a portrait painter, delving into each sitter as an adventure in representation rather than a crime scene, reflects the same interest in the minutiae of human life as detective work, including its tragedies and pains (e.g., the woman with a hunchback), but it does so from an aesthetic point of view that Snow’s life path had never allowed him to express. We would note that, in the course of his investigation of and writing about Beckwith, Snow literally actualized or realized this other, softer—we might say “more right-brained”—side of his personality. (Snow also discovered that Beckwith, like him, had harbored certain disappointments and misgivings about his career, thus delving into this 19th-century artist’s life might have been like gazing into a strange kind of mirror, indeed almost a “bizarro” version of himself.)

Snow’s “past life regression” was thus, in all likelihood, really a precognitive experience of a richly rewarding midlife journey of personal growth and conversion toward an exciting—as well as reassuring—new way of thinking. Besides opening him to his previously unexpressed artistic side, it carried along with it the implication of immortality, which is something that everyone in midlife becomes highly concerned with. But we should not miss here how prone to (self-)deception and manipulation the therapeutic context may be around issues of anomalous memory, particularly when it involves techniques like trance. As has been shown by Jack Brewer in his recent The Greys Have Been Framed, the whole field of alien abduction “research” also has a lot to answer for, in this regard.

The fact that Snow was effectively “converted” by his experience to a new metaphysics (that of reincarnation) suggests to me that misrecognized precognition could be a powerful, hitherto unexplored model of religious conversion and conviction, a possibility I will explore in future posts.

Postscript

Detective Snow made an unfortunate mistake in his investigation: failing to purchase the hunchback painting (which the gallery owner promised he could have “for a reasonable price”). Even if it were expensive, it would have been worth it, establishing an essential habit I have discussed in previous posts: honoring and commemorating your psi (or more generally paranormal) experiences, even when it entails some kind of sacrifice.

When you establish a habit of honoring your psi experiences—in my case, it often involves a usually inexpensive purchase of some dreamed-about book on eBay, or taking the time to watch a dreamed-about TV show or movie—you are in fact creating the conditions for precognitive events to manifest more and more. Commemoration is part of the reward and “post-selection” that the precognitive faculty orients toward. Being a prophet means habitually or even ritualistically honoring your prophecy when it is fulfilled; that moment of “honoring” is frequently the temporal terminus of the time loop, the wellspring of prophetic jouissance.

NOTES

* An interesting detail in Chiang’s story that is left out of the film is that the crucial clue to unraveling the heptapods’ mindset and language comes from Fermat’s principle of least time, according to which light always takes the fastest possible path to its destination. It is the rule that accounts for refraction of light through different mediums like water or glass, and it is another example of a physical principle that makes no sense in the absence of retrocausation, since photons need to “know” where they are going in order to take the right path. Had I known about Fermat’s principle, I would have listed it among the various examples of retrocausation-suggestive phenomena in my last post. The sure tip-off of such phenomena is that they compel us to ask how particles or photons “know” what to do before they do it. (Thanks to Chris Savia, a real-life heptapod, for encouraging me to read Chiang’s story.)

** Recovery of repressed memories through hypnosis is total BS, as hopefully most anomalists are by now aware … although I suspect they aren’t. First, there is little evidence that ordinary traumas are “repressed” in the way that Freud suggested; people who have been sexually abused as children and whose abuse can be corroborated typically remember these events spontaneously, for instance after seeing a news report that puts a new “adult” framing on what until then had been a baffling and hard-to-understand childhood event. “Memories” recovered in hypnosis, on the other hand, are typically much less easily corroborated, suggesting they are not memories but something else. Critics of regression therapy point to a robust research literature in memory distortion and creation of false memories: Trance-induced experiences may be the product of a collusion—likely unconscious and unintended but nevertheless extremely dangerous—between the subject and the therapist. But trance is also a highly psi-conducive state, leading me to suspect that much of the supposed abduction material produced in hypnosis may be precognition of future events given a sci-fi-inflected framing by the therapist’s or their own cultural expectations.

Thanks to Eric at: http://thenightshirt.com

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo