History changer? A 124,000-year-old thigh bone contains MODERN DNA

Researchers have discovered that a 124,000-year-old bone contains MODERN DNA. According to experts, the thigh bone could force us to completely rewrite everything we thought we know about our origins and human history.

The startling new discovery—a Neanderthal femur bone—discovered some 80 years ago is forcing experts to rethink everything they thought they knew about humans on our planet.

A new study published in the journal Nature Communications explains that a 124,000-year-old Neanderthal fossil—dug up in Germany from the Hohlenstein-Stadel Cave—contains MODERN DNA. Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and the University of Tübingen analyzed mitochondrial DNA from the femur bone.

This discovery indicates that the ‘out of Africa’ migration occurred much sooner than experts thought—around 270,000 years ago, forcing us to rewrite everything we thought we knew about our species’ origins.

“We are realizing more and more that the evolutionary history of modern and archaic humans was a lot more reticulated than we would have thought 10 years ago,” co-author Fernando Racimo of the New York Genome Center told New Scientist. “This and previous findings are lending support to models with frequent interbreeding events.”

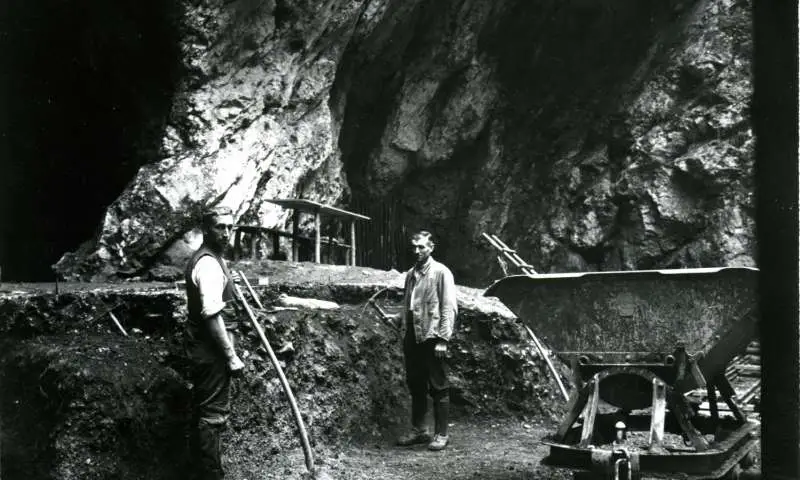

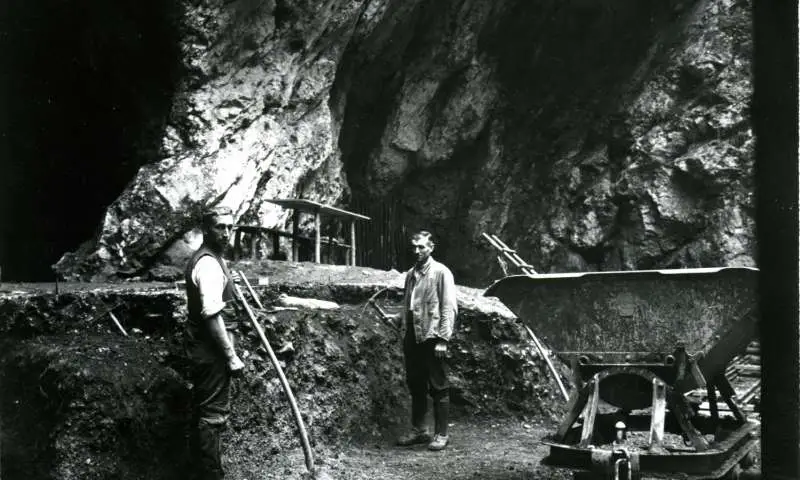

During excavations near the entrance of Hohlenstein-Stadel cave in southwestern Germany in 1937, a 124,000-year-old Neanderthal femur was discovered. Now its mitochondrial DNA was analyzed and provides a timeline for a suggested migration of hominins out of Africa before 220,000 years ago. Credit: © Photo Museum Ulm

The Genetic DATA obtained by scientists indicates that the bone belonged to a Neanderthal some 124,000 years ago and that hominins migrated out of Africa after the ancestors of Neanderthals arrived in Europe. Furthermore, scientists are convinced that these hominins interbred with Neanderthals between 220,000 and 470,000 years ago—300,000 years later than previously thought.

“The bone, which shows evidence of being gnawed on by a large carnivore, provided mitochondrial genetic data that showed it belongs to the Neanderthal branch,” explains Cosimo Posth of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, lead author of the study.

It is noteworthy to mention that traditional radiocarbon dating did not work to obtain the approximate age of the femur. Mutational rates allowed experts to calculate that these Neanderthals split apart from each other between 316,000 and 219,000 years ago. Experts found that it displays a different mitochondrial lineage than the Neanderthals previously studied.

As noted by Phys.org, this makes this Neanderthal specimen—designated HST by the researchers—among the oldest to have its mitochondrial DNA analyzed to date.

The new discoveries also suggest that the Neanderthal population was much larger in size than estimated and with a greater mitochondrial diversity.

Experts believe that after the divergence of Neanderthals and modern human mitochondrial DNA occurred—but before the HST and other Neanderthals split—a group of hominins migrated from Africa to Europe and introduced their mitochondrial DNA to the Neanderthal population. This is believed to have occurred between 470,000 and 220,000 years ago.

“Despite the large interval, these dates provide a temporal window for possible hominin connectivity and interaction across the two continents in the past,” says Posth.

This influx of hominins would have been small enough that it did not result in a large impact on the Neanderthals’ nuclear DNA, but it would have been large enough to replace the existing mitochondrial lineage of Neanderthals, more similar to the Denisovans, with a type more similar to modern humans.

“This scenario reconciles the discrepancy in the nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA phylogenies of archaic hominins and the inconsistency of the modern human-Neanderthal population split time estimated from nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA,” explains Johannes Krause, also of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, senior author of the study.

(H/T Phys.org)

Reference: IFLScience

Thanks to: https://www.ancient-code.com

Researchers have discovered that a 124,000-year-old bone contains MODERN DNA. According to experts, the thigh bone could force us to completely rewrite everything we thought we know about our origins and human history.

The startling new discovery—a Neanderthal femur bone—discovered some 80 years ago is forcing experts to rethink everything they thought they knew about humans on our planet.

A new study published in the journal Nature Communications explains that a 124,000-year-old Neanderthal fossil—dug up in Germany from the Hohlenstein-Stadel Cave—contains MODERN DNA. Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and the University of Tübingen analyzed mitochondrial DNA from the femur bone.

This discovery indicates that the ‘out of Africa’ migration occurred much sooner than experts thought—around 270,000 years ago, forcing us to rewrite everything we thought we knew about our species’ origins.

“We are realizing more and more that the evolutionary history of modern and archaic humans was a lot more reticulated than we would have thought 10 years ago,” co-author Fernando Racimo of the New York Genome Center told New Scientist. “This and previous findings are lending support to models with frequent interbreeding events.”

During excavations near the entrance of Hohlenstein-Stadel cave in southwestern Germany in 1937, a 124,000-year-old Neanderthal femur was discovered. Now its mitochondrial DNA was analyzed and provides a timeline for a suggested migration of hominins out of Africa before 220,000 years ago. Credit: © Photo Museum Ulm

The Genetic DATA obtained by scientists indicates that the bone belonged to a Neanderthal some 124,000 years ago and that hominins migrated out of Africa after the ancestors of Neanderthals arrived in Europe. Furthermore, scientists are convinced that these hominins interbred with Neanderthals between 220,000 and 470,000 years ago—300,000 years later than previously thought.

“The bone, which shows evidence of being gnawed on by a large carnivore, provided mitochondrial genetic data that showed it belongs to the Neanderthal branch,” explains Cosimo Posth of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, lead author of the study.

It is noteworthy to mention that traditional radiocarbon dating did not work to obtain the approximate age of the femur. Mutational rates allowed experts to calculate that these Neanderthals split apart from each other between 316,000 and 219,000 years ago. Experts found that it displays a different mitochondrial lineage than the Neanderthals previously studied.

As noted by Phys.org, this makes this Neanderthal specimen—designated HST by the researchers—among the oldest to have its mitochondrial DNA analyzed to date.

The new discoveries also suggest that the Neanderthal population was much larger in size than estimated and with a greater mitochondrial diversity.

Experts believe that after the divergence of Neanderthals and modern human mitochondrial DNA occurred—but before the HST and other Neanderthals split—a group of hominins migrated from Africa to Europe and introduced their mitochondrial DNA to the Neanderthal population. This is believed to have occurred between 470,000 and 220,000 years ago.

“Despite the large interval, these dates provide a temporal window for possible hominin connectivity and interaction across the two continents in the past,” says Posth.

This influx of hominins would have been small enough that it did not result in a large impact on the Neanderthals’ nuclear DNA, but it would have been large enough to replace the existing mitochondrial lineage of Neanderthals, more similar to the Denisovans, with a type more similar to modern humans.

“This scenario reconciles the discrepancy in the nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA phylogenies of archaic hominins and the inconsistency of the modern human-Neanderthal population split time estimated from nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA,” explains Johannes Krause, also of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, senior author of the study.

(H/T Phys.org)

Reference: IFLScience

Thanks to: https://www.ancient-code.com

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo