Natural Wetland in India Filters 198 Million Gallons of Waste Every Day Without Chemicals

Amanda Froelich

What if it was possible to filter human waste in a sanitary and eco-friendly way? We have news for you — it is. In the East Kolkata Wetlands (EKW) in India, 198 million gallons of human waste is treated every day through a process called bioremediation. Not only do the wetlands keep Kolkata sewage-free, they support a fertile aquatic garden and protect the low-lying city from flooding.

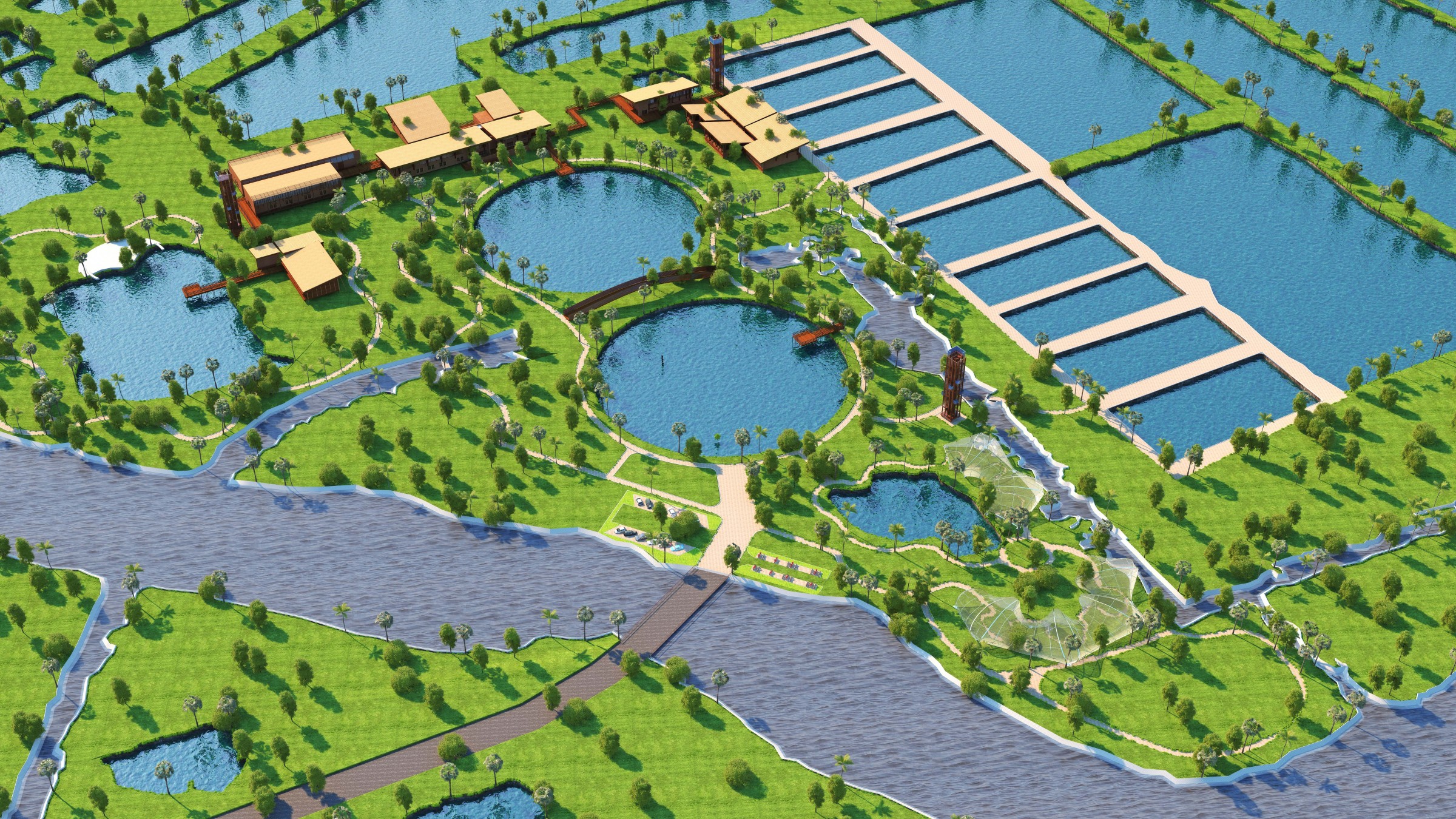

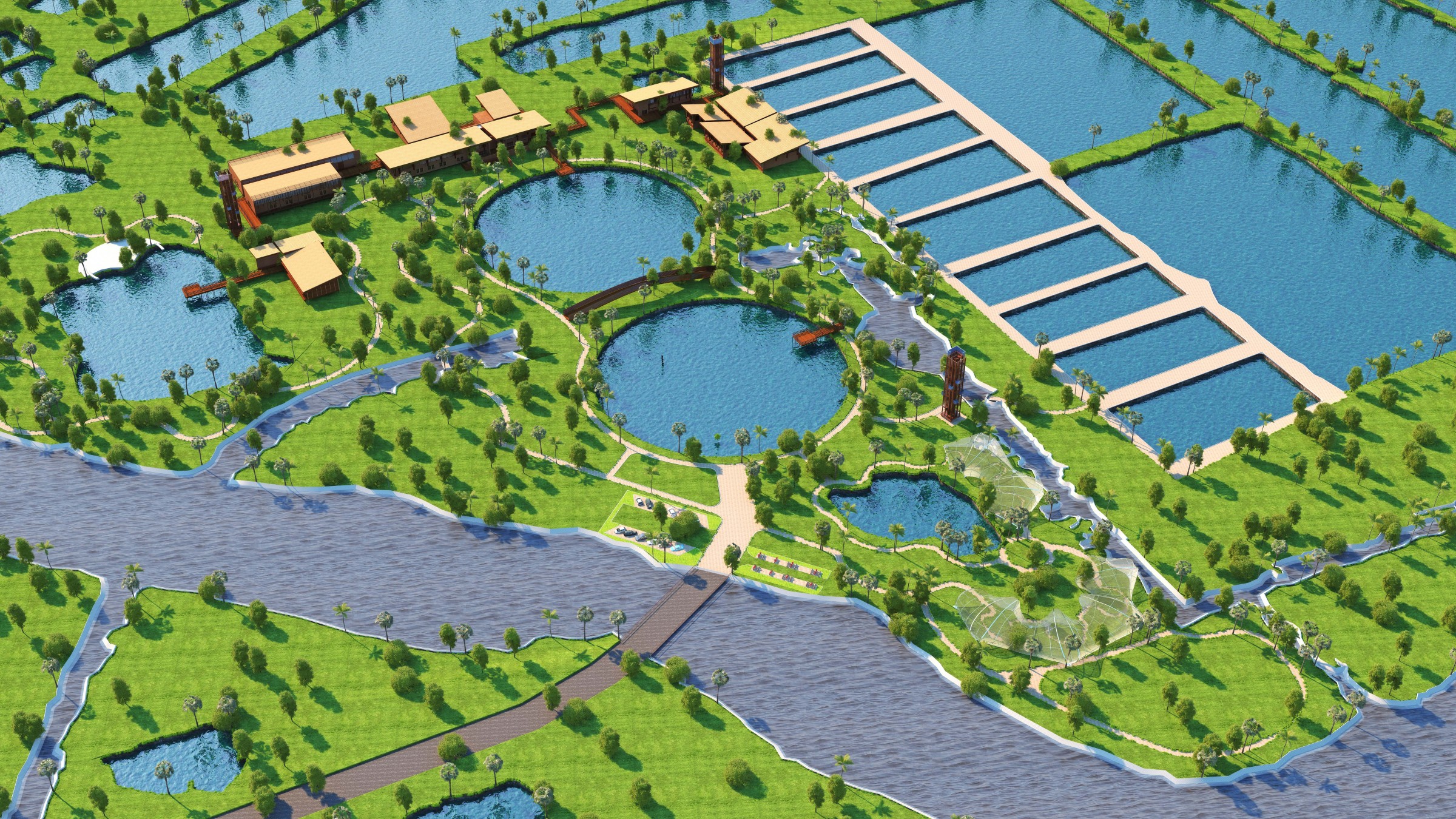

Credit: Ramsar.org

As The Better India reports, the EKW is the world’s only fully functional organic sewage management system. What was once was a patchwork of low-lying salt marshes and slow-running rivers is now a vast network of man-made wetlands which are bordered by green embankments.

The “kidneys of Kolkata” are maintained by farmers and fisherman. Each day, the wetlands receive nearly 750 million liters of the city’s waste each day. With the help of sunshine, oxygen, and microbial action, the sewage is organically treated.

Credit: YouTube

A parabolic fish gate is in place to separate the wetland water from the wastewater. Its purpose is to prevent fish from swimming into the oxygen-deprived urban waste water. There, they would die.

Credit: ArchiPrix

It takes less than 20 days for nature to do its work. Organic waste, located in the inlets, settles down where it partly decomposes in the warm shallow water. Then, through a series of biological steps, the waste is converted into fish food. Soil bacteria, macro-algae, plant bacteria, and plants themselves all contribute the decomposition of the waste. The ecological processes are accelerated when sunlight penetrates the settled water.

After the process of bioremediation, the purified, nutrient-rich water is channeled into ponds, called bheries, where algae and fish thrive. Some of the water is also used to grow paddy and vegetables on the banks of the wetlands.

Credit: YouTube

In addition to keeping Kolkata sewage-free and providing fertilizer to grow crops, the wetlands act as a natural flood control system. When floods threaten Kolkata, gravitational forces take the discharge eastward of the city, into the wetlands. In a way, the EKW serves as a natural spill basin. This function is essential during the monsoon season when the entire Gangetic delta is at-risk of flooding.

Despite their usefulness, the wetlands are at risk. A voracious appetite for real estate is threatening the fish ponds, where buyers seek to build. To raise awareness about this conundrum and the enormous value of the wetland’s environmental services, former city sanitation engineer Dhrubajyoti Ghosh has dedicated himself to campaigning for the unique ecosystem. Over the past couple of decades, he has developed technology options from the traditional practice of wastewater aquaculture. So far, four other towns have adopted the wastewater designs.

Credit: Ramsar.org

To this day, Ghosh works to preserve the EKW. He says,

“I am still learning how this delicate ecosystem works, how to further refine it, and why some places are better suited than others. I am happy to give any advice or help absolutely free, this is the best system of its kind in the world and could be helping millions of people. If I have failed in one thing it is this; not enough people know about it or are benefiting from it.”

https://youtu.be/zv03OYNpjmI

Thanks to: https://themindunleashed.com

Amanda Froelich

- Mar 19, 2018

What if it was possible to filter human waste in a sanitary and eco-friendly way? We have news for you — it is. In the East Kolkata Wetlands (EKW) in India, 198 million gallons of human waste is treated every day through a process called bioremediation. Not only do the wetlands keep Kolkata sewage-free, they support a fertile aquatic garden and protect the low-lying city from flooding.

Credit: Ramsar.org

As The Better India reports, the EKW is the world’s only fully functional organic sewage management system. What was once was a patchwork of low-lying salt marshes and slow-running rivers is now a vast network of man-made wetlands which are bordered by green embankments.

The “kidneys of Kolkata” are maintained by farmers and fisherman. Each day, the wetlands receive nearly 750 million liters of the city’s waste each day. With the help of sunshine, oxygen, and microbial action, the sewage is organically treated.

Credit: YouTube

How it works

Urban waste is routed through a maze of small inlets, each managed by a fishery cooperative. The cooperatives are in charge of the inflow of the wastewater. After the sewage settles, only the clear top layers of water flow into the shallow wetland.A parabolic fish gate is in place to separate the wetland water from the wastewater. Its purpose is to prevent fish from swimming into the oxygen-deprived urban waste water. There, they would die.

Credit: ArchiPrix

It takes less than 20 days for nature to do its work. Organic waste, located in the inlets, settles down where it partly decomposes in the warm shallow water. Then, through a series of biological steps, the waste is converted into fish food. Soil bacteria, macro-algae, plant bacteria, and plants themselves all contribute the decomposition of the waste. The ecological processes are accelerated when sunlight penetrates the settled water.

After the process of bioremediation, the purified, nutrient-rich water is channeled into ponds, called bheries, where algae and fish thrive. Some of the water is also used to grow paddy and vegetables on the banks of the wetlands.

Credit: YouTube

In addition to keeping Kolkata sewage-free and providing fertilizer to grow crops, the wetlands act as a natural flood control system. When floods threaten Kolkata, gravitational forces take the discharge eastward of the city, into the wetlands. In a way, the EKW serves as a natural spill basin. This function is essential during the monsoon season when the entire Gangetic delta is at-risk of flooding.

Despite their usefulness, the wetlands are at risk. A voracious appetite for real estate is threatening the fish ponds, where buyers seek to build. To raise awareness about this conundrum and the enormous value of the wetland’s environmental services, former city sanitation engineer Dhrubajyoti Ghosh has dedicated himself to campaigning for the unique ecosystem. Over the past couple of decades, he has developed technology options from the traditional practice of wastewater aquaculture. So far, four other towns have adopted the wastewater designs.

Credit: Ramsar.org

To this day, Ghosh works to preserve the EKW. He says,

“I am still learning how this delicate ecosystem works, how to further refine it, and why some places are better suited than others. I am happy to give any advice or help absolutely free, this is the best system of its kind in the world and could be helping millions of people. If I have failed in one thing it is this; not enough people know about it or are benefiting from it.”

https://youtu.be/zv03OYNpjmI

Thanks to: https://themindunleashed.com

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo