Federal Agencies and Public Health Experts Refuse to Declare Autism a National Health Crisis

Enough Already: Autism Needs to Be Declared a National Health Crisis

by the World Mercury Project TeamIt is both astonishing and insulting that, nearly three decades in, federal agencies and public health experts persist in denying and refusing to tackle our nation’s staggering autism epidemic.

With typical dismissiveness (and a straight face), one group of pediatric researchers recently had the temerity to put the word “epidemic” in quotes while endorsing the charade that the rising prevalence of autism is attributable to broader diagnostic criteria, increased awareness and “the inclusion of milder neurodevelopmental differences bordering on normality.”

The government’s own surveys—as well as parents, school systems and municipal budgets—tell an entirely different story, however.

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) began skyrocketing in the late 1980s, concurrent with a massive expansion of the childhood vaccine schedule and a corresponding increase in children’s exposure to neurotoxic vaccine ingredients such as mercury and aluminum.

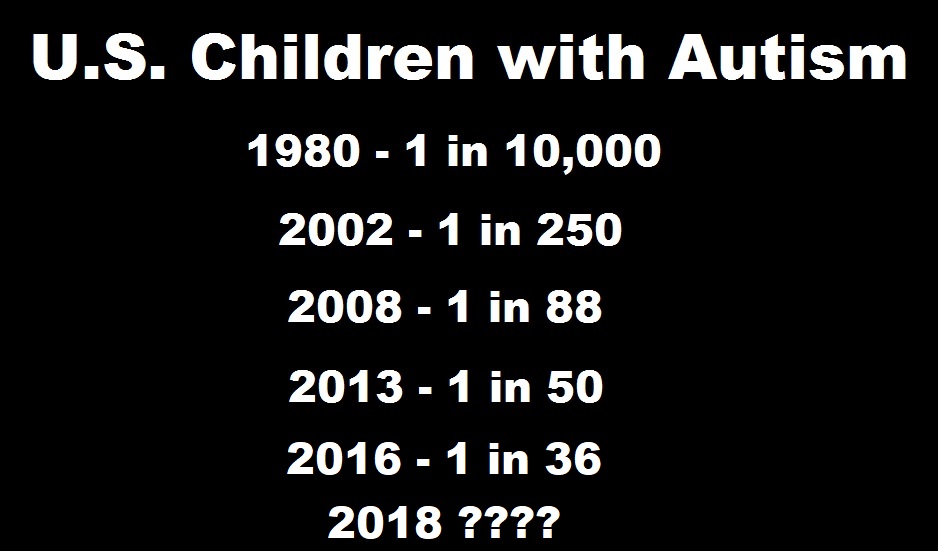

Using data from the U.S. Office of Special Education Programs, a 2005 study published in Pediatrics reported that autism prevalence went from roughly 1 in 2,850 ten-year-olds born in 1982 (0.035%) to about 1 in 550 ten-year-olds born in 1990 (0.183%).

In the early 2000s, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began monitoring ASD prevalence (and changes in prevalence over time) through its Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network, an active surveillance system that gathers data from roughly a dozen sites around the U.S. to ascertain ASD prevalence in 8-year-olds. Over the first decade of surveillance, the CDC reported that ASD prevalence rose by 123%.

As the above table illustrates, the ADDM program has one major shortcoming, which is the lag time between data collection, analysis and publication of prevalence data. For example, the data published in 2014 took four years to analyze and captured ASD prevalence for the cohort born 12 years earlier (i.e., children born in 2002 who were eight years old in 2010). CDC did not report the prevalence estimates for children born in 1992 until 2007.

The ADDM program has other acknowledged limitations as well, including:

- Constant changes in the number and location of surveillance sites

- A reliance on educational records that are not consistently available at all surveillance sites (which would tend to underestimate true prevalence)

- Failure to differentiate between ASD subgroups as an indicator of severity (but with differentiation by IQ, with 70 as the cutoff)

For these reasons, some observers believe that data routinely published by the National Center for Health Statistics more accurately represent the true autism picture. The Center’s prevalence data are based on parental reports from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).

As of 2014, NHIS data indicated that 1 in 45 children aged 3-17 years had been diagnosed with ASD (2.24%), and by 2016 this number was 1 in 36 (2.76%)—a 23% increase over the two-year period—and a far cry from the 1 in 550 reported from other data sources in 1990.

A health care and education burden

The CDC is due to release its latest ADDM surveillance numbers. Will our federal health agencies continue to downplay the numbers’ significance, as they have done each time the data show a rise in ASD prevalence? Or will they finally sound an alarm and make it a top priority to find out what is causing this epidemic in our children?

At a societal level, ASD imposes a substantial economic burden, especially on the health care and education sectors.

A study by Harvard researchers found that ASD was associated with over $17,000 more in health care and non-health-care costs annually per child. School systems (and thus taxpayers) carry a large portion of this additional financial burden to cover the special education services used by 76% of ASD children versus 7% of children without ASD.

Over the decade from 2005-2015, the number of students with ASD (ages 6-21) rose by 165% nationally.

At the family level, the average lifetime cost of caring for a child with autism (including the cost of lost wages) ranges from an estimated $1.4 to $2.4 million (depending on the level of intellectual disability), representing “a huge hit on families.”

Individuals with ASD also face vastly increased risks of medical comorbidities, including atopic disorders such as allergies and asthma, seizures, gastrointestinal problems, cancer and decreased life expectancy.

A study that compared individuals with autism to the general population found elevated death rates in the ASD group for causes of death such as seizures and accidental drowning or suffocation and noted overall reduced life expectancy “even for persons who are fully ambulatory” and have only “mild” intellectual disability.

An urgent situation

Over the years, many of the CDC’s bulletins about ASD prevalence have placidly reported that “ASDs are more common than was believed previously.”However, the continued dramatic rise in ASD prevalence and autism’s heavy burden on individuals, families, schools and wider society call for a far greater sense of urgency.

Autism must be recognized as a national crisis.

As of this writing (April 2018), the CDC is due to release its latest ADDM surveillance numbers.

Will our federal health agencies continue to downplay the numbers’ significance, as they have done each time the data show a rise in ASD prevalence? Or will they finally sound an alarm and make it a top priority to find out what is causing this epidemic in our children?

No one—and not least the agencies that are supposed to be looking out for children’s best interests—can afford to be complacent any longer about this unjustifiably neglected public health emergency.

Read the full article at WorldMercuryProject.org.

Thanks to: http://vaccineimpact.com

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo