Gravitational Waves Leave Observable Aftereffects in Universe

May 10, 2019

Gravitational waves are ‘ripples’ in space-time caused by some of the most violent and energetic processes in the Universe. Albert Einstein predicted the existence of gravitational waves in 1916 in his general theory of relativity. New research shows those waves leave behind plenty of ‘memories’ that could help detect them even after they’ve passed.

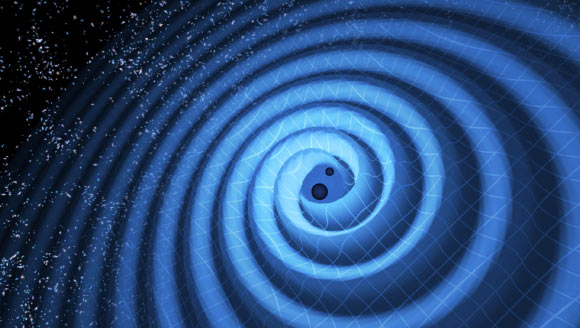

Gravitational waves observed by Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) twin detectors were produced during the final fraction of a second of the merger of two black holes to produce a single, more massive spinning black hole. Image credit: T. Pyle / LIGO.

“That gravitational waves can leave permanent changes to a detector after the gravitational waves have passed is one of the rather unusual predictions of general relativity,” said Alexander Grant, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Physics at Cornell University.

Physicists have long known that gravitational waves leave a memory on the particles along their path, and have identified five such memories.

Grant and colleagues have now found three more aftereffects of the passing of a gravitational wave, ‘persistent gravitational wave observables’ that could someday help identify waves passing through the Universe.

“Each new observable provides different ways of confirming the theory of general relativity and offers insight into the intrinsic properties of gravitational waves,” Grant said.

Those properties could help extract information from the Cosmic Microwave Background, the radiation left over from the Big Bang.

“We didn’t anticipate the richness and diversity of what could be observed,” said Professor Éanna Flanagan, also from Cornell University.

The team identified three observables that show the effects of gravitational waves in a flat region in space-time that experiences a burst of gravitational waves, after which it returns again to being a flat region.

The first observable, ‘curve deviation,’ is how much two accelerating observers separate from one another, compared to how observers with the same accelerations would separate from one another in a flat space undisturbed by a gravitational wave.

The second observable, ‘holonomy,’ is obtained by transporting information about the linear and angular momentum of a particle along two different curves through the gravitational waves, and comparing the two different results.

The third looks at how gravitational waves affect the relative displacement of two particles when one of the particles has an intrinsic spin.

Each of these observables is defined by the physicists in a way that could be measured by a detector.

“The detection procedures for curve deviation and the spinning particles are relatively straightforward to perform, requiring only a means of measuring separation and for the observers to keep track of their respective accelerations,” they said.

“Detecting the holonomy observable would be more difficult, requiring two observers to measure the local curvature of spacetime (potentially by carrying around small gravitational wave detectors themselves).”

“Given the size needed for NSF’s Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory to detect even one gravitational wave, the ability to detect holonomy observables is beyond the reach of current science.”

“But we’ve seen a lot of exciting things already with gravitational waves, and we will see a lot more. There are even plans to put a gravitational wave detector in space that would be sensitive to different sources than LIGO,” Flanagan said.

The team’s work was published in the journal Physical Review D.

_____

Éanna É. Flanagan et al. 2019. Persistent gravitational wave observables: General framework. Phys. Rev. D 99 (8): 084044; doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.99.084044

Thanks to: http://www.sci-news.com

May 10, 2019

Gravitational waves are ‘ripples’ in space-time caused by some of the most violent and energetic processes in the Universe. Albert Einstein predicted the existence of gravitational waves in 1916 in his general theory of relativity. New research shows those waves leave behind plenty of ‘memories’ that could help detect them even after they’ve passed.

Gravitational waves observed by Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) twin detectors were produced during the final fraction of a second of the merger of two black holes to produce a single, more massive spinning black hole. Image credit: T. Pyle / LIGO.

“That gravitational waves can leave permanent changes to a detector after the gravitational waves have passed is one of the rather unusual predictions of general relativity,” said Alexander Grant, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Physics at Cornell University.

Physicists have long known that gravitational waves leave a memory on the particles along their path, and have identified five such memories.

Grant and colleagues have now found three more aftereffects of the passing of a gravitational wave, ‘persistent gravitational wave observables’ that could someday help identify waves passing through the Universe.

“Each new observable provides different ways of confirming the theory of general relativity and offers insight into the intrinsic properties of gravitational waves,” Grant said.

Those properties could help extract information from the Cosmic Microwave Background, the radiation left over from the Big Bang.

“We didn’t anticipate the richness and diversity of what could be observed,” said Professor Éanna Flanagan, also from Cornell University.

The team identified three observables that show the effects of gravitational waves in a flat region in space-time that experiences a burst of gravitational waves, after which it returns again to being a flat region.

The first observable, ‘curve deviation,’ is how much two accelerating observers separate from one another, compared to how observers with the same accelerations would separate from one another in a flat space undisturbed by a gravitational wave.

The second observable, ‘holonomy,’ is obtained by transporting information about the linear and angular momentum of a particle along two different curves through the gravitational waves, and comparing the two different results.

The third looks at how gravitational waves affect the relative displacement of two particles when one of the particles has an intrinsic spin.

Each of these observables is defined by the physicists in a way that could be measured by a detector.

“The detection procedures for curve deviation and the spinning particles are relatively straightforward to perform, requiring only a means of measuring separation and for the observers to keep track of their respective accelerations,” they said.

“Detecting the holonomy observable would be more difficult, requiring two observers to measure the local curvature of spacetime (potentially by carrying around small gravitational wave detectors themselves).”

“Given the size needed for NSF’s Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory to detect even one gravitational wave, the ability to detect holonomy observables is beyond the reach of current science.”

“But we’ve seen a lot of exciting things already with gravitational waves, and we will see a lot more. There are even plans to put a gravitational wave detector in space that would be sensitive to different sources than LIGO,” Flanagan said.

The team’s work was published in the journal Physical Review D.

_____

Éanna É. Flanagan et al. 2019. Persistent gravitational wave observables: General framework. Phys. Rev. D 99 (8): 084044; doi: 10.1103/PhysRevD.99.084044

Thanks to: http://www.sci-news.com

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo