Humans Interbred with Four Extinct Hominin Species, Research Finds

Jul 29, 2019

|

As anatomically modern Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa and around the rest of the world, they met and interbred with at least four different hominin species, according to new research from the University of Adelaide, Australia. Strikingly, of these hominins, only Neanderthals and Denisovans are currently known; the others remain unnamed and have only been detected as traces of DNA surviving in different modern populations.

Reconstruction of Homo floresiensis, an extinct hominin species that lived on the Indonesian island of Flores between 74,000 and 18,000 years ago. Image credit: Elisabeth Daynes.

“Each of us carry within ourselves the genetic traces of these past mixing events,” said Dr. João Teixeira, co-author of a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“These archaic groups were widespread and genetically diverse, and they survive in each of us. Their story is an integral part of how we came to be.”

“For example, all present-day populations show about 2% of Neanderthal ancestry which means that Neanderthal mixing with the ancestors of modern humans occurred soon after they left Africa, probably around 50,000 to 55,000 years ago somewhere in the Middle East.”

But as the ancestors of modern humans traveled further east they met and mixed with at least four other groups of archaic humans.

“Island Southeast Asia was already a crowded place when what we call modern humans first reached the region just before 50,000 years ago,” Dr. Teixeira said.

“At least three other archaic human groups appear to have occupied the area, and the ancestors of modern humans mixed with them before the archaic humans became extinct.”

In their new research, Dr. Teixeira and his colleague, Professor Alan Cooper, analyzed genetic, archaeological and fossil evidence as well as additional information from reconstructed migration routes and fossil vegetation records.

The scientists found there was a mixing event in the vicinity of southern Asia between anatomically modern humans and a group they named Extinct Hominin 1 (EH1).

Other interbreeding occurred with Denisovans in Island Southeast Asia and the Philippines, and with another group — named Extinct Hominin 2 (EH2) — in Flores, Indonesia.

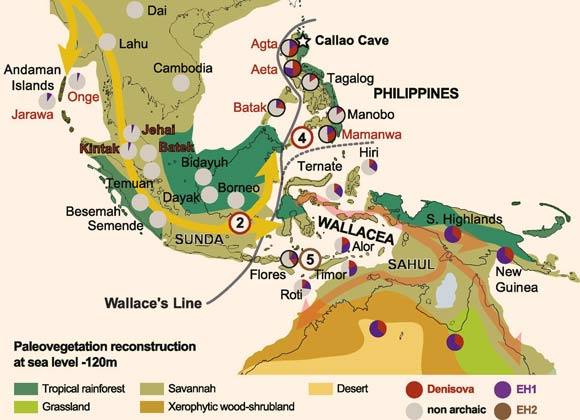

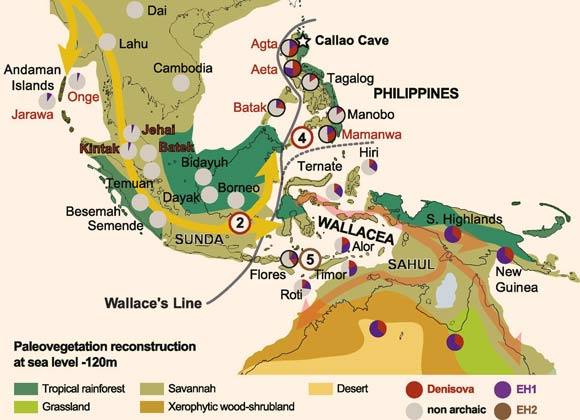

The inferred route of the movement of anatomically modern humans through Island Southeast Asia around 50,000 years ago (yellow and red arrows): modern-day hunter-gatherer populations with genetic data are shown in red, and farming populations are shown in black; the estimated genomic content of EH1 (purple), Denisovan (red), EH2 (brown), and nonarchaic (gray) in modern-day populations is shown in pie charts, as a relative proportion to that seen in Australo-Papuans (full circles); gray all populations containing large amounts of Denisovan genomic content are found east of Wallace’s Line; independent introgression events with Denisovan groups are inferred for both the common ancestor of Australo-Papuan, Philippines, and ISEA populations (red circled 2) and, separately, for the Philippines (red circled 4); the signal for a separate introgression with an unknown hominin on Flores, recorded in genomic data from modern-day populations, remains less secure (brown-circled 5); the precise location of introgression events 2, 4, and 5 currently remains unknown. Image credit: Teixeira & Cooper, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1904824116.

“We knew the story out of Africa wasn’t a simple one, but it seems to be far more complex than we have contemplated,” Dr. Teixeira said.

“The Island Southeast Asia region was clearly occupied by several archaic human groups, probably living in relative isolation from each other for hundreds of thousands of years before the ancestors of modern humans arrived.”

“The timing also makes it look like the arrival of modern humans was followed quickly by the demise of the archaic human groups in each area.”

_____

João C. Teixeira & Alan Cooper. Using hominin introgression to trace modern human dispersals. PNAS, published online July 12, 2019; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1904824116

Thanks to: http://www.sci-news.com

Jul 29, 2019

|

As anatomically modern Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa and around the rest of the world, they met and interbred with at least four different hominin species, according to new research from the University of Adelaide, Australia. Strikingly, of these hominins, only Neanderthals and Denisovans are currently known; the others remain unnamed and have only been detected as traces of DNA surviving in different modern populations.

Reconstruction of Homo floresiensis, an extinct hominin species that lived on the Indonesian island of Flores between 74,000 and 18,000 years ago. Image credit: Elisabeth Daynes.

“Each of us carry within ourselves the genetic traces of these past mixing events,” said Dr. João Teixeira, co-author of a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“These archaic groups were widespread and genetically diverse, and they survive in each of us. Their story is an integral part of how we came to be.”

“For example, all present-day populations show about 2% of Neanderthal ancestry which means that Neanderthal mixing with the ancestors of modern humans occurred soon after they left Africa, probably around 50,000 to 55,000 years ago somewhere in the Middle East.”

But as the ancestors of modern humans traveled further east they met and mixed with at least four other groups of archaic humans.

“Island Southeast Asia was already a crowded place when what we call modern humans first reached the region just before 50,000 years ago,” Dr. Teixeira said.

“At least three other archaic human groups appear to have occupied the area, and the ancestors of modern humans mixed with them before the archaic humans became extinct.”

In their new research, Dr. Teixeira and his colleague, Professor Alan Cooper, analyzed genetic, archaeological and fossil evidence as well as additional information from reconstructed migration routes and fossil vegetation records.

The scientists found there was a mixing event in the vicinity of southern Asia between anatomically modern humans and a group they named Extinct Hominin 1 (EH1).

Other interbreeding occurred with Denisovans in Island Southeast Asia and the Philippines, and with another group — named Extinct Hominin 2 (EH2) — in Flores, Indonesia.

The inferred route of the movement of anatomically modern humans through Island Southeast Asia around 50,000 years ago (yellow and red arrows): modern-day hunter-gatherer populations with genetic data are shown in red, and farming populations are shown in black; the estimated genomic content of EH1 (purple), Denisovan (red), EH2 (brown), and nonarchaic (gray) in modern-day populations is shown in pie charts, as a relative proportion to that seen in Australo-Papuans (full circles); gray all populations containing large amounts of Denisovan genomic content are found east of Wallace’s Line; independent introgression events with Denisovan groups are inferred for both the common ancestor of Australo-Papuan, Philippines, and ISEA populations (red circled 2) and, separately, for the Philippines (red circled 4); the signal for a separate introgression with an unknown hominin on Flores, recorded in genomic data from modern-day populations, remains less secure (brown-circled 5); the precise location of introgression events 2, 4, and 5 currently remains unknown. Image credit: Teixeira & Cooper, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1904824116.

“We knew the story out of Africa wasn’t a simple one, but it seems to be far more complex than we have contemplated,” Dr. Teixeira said.

“The Island Southeast Asia region was clearly occupied by several archaic human groups, probably living in relative isolation from each other for hundreds of thousands of years before the ancestors of modern humans arrived.”

“The timing also makes it look like the arrival of modern humans was followed quickly by the demise of the archaic human groups in each area.”

_____

João C. Teixeira & Alan Cooper. Using hominin introgression to trace modern human dispersals. PNAS, published online July 12, 2019; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1904824116

Thanks to: http://www.sci-news.com

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo