United States Electoral College

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigation Jump to search

This article is about the electoral college of the United States. For electoral colleges in general, see Electoral college. For other uses and regions, see Electoral college (disambiguation).

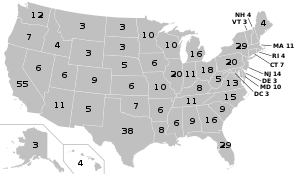

Electoral votes allocated to each state and to the District of Columbia for the 2012, 2016 and 2020 presidential elections, based on populations from the 2010 Census (Total: 538)

Composite Electoral College vote tally for the 2016 presidential election. The total number of votes cast was 538, of which Donald Trump received 304 votes (●), Hillary Clinton received 227 (●), Colin Powell received 3 (●), Bernie Sanders received 1 (●), John Kasich received 1 (●), Ron Paul received 1 (●) and Faith Spotted Eagle received 1 (●). The total of electors do not meet together to vote, but rather separately meet in their individual jurisdictions.

Following the nationwide presidential election, which takes place the Tuesday after the first Monday of November, each state counts its popular votes according to that state's laws to designate presidential electors. In forty-eight states and D.C., the winner of the plurality of the statewide vote receives all of that state's electors; in Maine and Nebraska, two electors are assigned in this manner and the remaining electors are allocated based on the plurality of votes in each congressional district.[7] States generally require electors to pledge to vote for that state's winner; to avoid faithless electors, most states have adopted various laws to enforce the elector's pledge.[8] Each state's electors meet in their respective state capital on the first Monday after the second Wednesday of December to cast their votes.[7] The results are counted by Congress, where they are tabulated in the first week of January before a joint meeting of the Senate and House of Representatives, presided over by the vice president, acting as president of the Senate.[7][9] Should a majority of votes not be cast for a candidate, the House turns itself into a presidential election session, where one vote is assigned to each of the fifty states. The elected president and vice president are inaugurated on January 20. While the electoral vote has generally given the same result as the popular vote, this has not been the case in several elections, most recently in the 2016 election.

The suitability of the Electoral College system is a matter of ongoing debate. Supporters of the Electoral College argue that it is fundamental to American federalism, that it requires candidates to appeal to voters outside large cities, increases the political influence of small states, preserves the two-party system, and makes the electoral outcome appear more legitimate than that of a nationwide popular vote.[10]

Opponents of the Electoral College argue that it can result in different candidates winning the popular and electoral vote (which occurred in two of the five presidential elections from 2000 to 2016); that it causes candidates to focus their campaigning disproportionately in a few "swing states"; and that its allocation of Electoral College votes gives citizens in less populated states (e.g., Wyoming) more voting power than those in more populous states (e.g., California).[11][12][13][14][15]

Contents

- 1 Background

- 2 History

- 2.1 Original plan

- 2.2 Evolution to the general ticket

- 2.3 Evolution of selection plans

- 2.4 Three-fifths clause and the role of slavery

- 2.5 Fourteenth Amendment

- 2.6 Meeting of electors

Background

The Constitutional Convention in 1787 used the Virginia Plan as the basis for discussions, as the Virginia proposal was the first. The Virginia Plan called for the Congress to elect the president.[16] Delegates from a majority of states agreed to this mode of election. After being debated, however, delegates came to oppose nomination by congress for the reason that it could violate the separation of powers. James Wilson then made motion for electors for the purpose of choosing the president.[17]Later in the convention, a committee formed to work out various details including the mode of election of the president, including final recommendations for the electors, a group of people apportioned among the states in the same numbers as their representatives in Congress (the formula for which had been resolved in lengthy debates resulting in the Connecticut Compromise and Three-Fifths Compromise), but chosen by each state "in such manner as its Legislature may direct". Committee member Gouverneur Morris explained the reasons for the change; among others, there were fears of "intrigue" if the president were chosen by a small group of men who met together regularly, as well as concerns for the independence of the president if he were elected by the Congress.[18]

However, once the Electoral College had been decided on, several delegates (Mason, Butler, Morris, Wilson, and Madison) openly recognized its ability to protect the election process from cabal, corruption, intrigue, and faction. Some delegates, including James Wilson and James Madison, preferred popular election of the executive.[19][20] Madison acknowledged that while a popular vote would be ideal, it would be difficult to get consensus on the proposal given the prevalence of slavery in the South:

The Convention approved the Committee's Electoral College proposal, with minor modifications, on September 6, 1787.[22] Delegates from states with smaller populations or limited land area such as Connecticut, New Jersey, and Maryland generally favored the Electoral College with some consideration for states.[23] At the compromise providing for a runoff among the top five candidates, the small states supposed that the House of Representatives with each state delegation casting one vote would decide most elections.[24]There was one difficulty however of a serious nature attending an immediate choice by the people. The right of suffrage was much more diffusive in the Northern than the Southern States; and the latter could have no influence in the election on the score of Negroes. The substitution of electors obviated this difficulty and seemed on the whole to be liable to the fewest objections.[21]

In The Federalist Papers, James Madison explained his views on the selection of the president and the Constitution. In Federalist No. 39, Madison argued the Constitution was designed to be a mixture of state-based and population-based government. Congress would have two houses: the state-based Senate and the population-based House of Representatives. Meanwhile, the president would be elected by a mixture of the two modes.[25]

Alexander Hamilton in Federalist No. 68 laid out what he believed were the key advantages to the Electoral College. The electors come directly from the people and them alone for that purpose only, and for that time only. This avoided a party-run legislature, or a permanent body that could be influenced by foreign interests before each election.[26] Hamilton explained the election was to take place among all the states, so no corruption in any state could taint "the great body of the people" in their selection. The choice was to be made by a majority of the Electoral College, as majority rule is critical to the principles of republican government. Hamilton argued that electors meeting in the state capitals were able to have information unavailable to the general public. Hamilton also argued that since no federal officeholder could be an elector, none of the electors would be beholden to any presidential candidate.[26]

Another consideration was the decision would be made without "tumult and disorder" as it would be a broad-based one made simultaneously in various locales where the decision-makers could deliberate reasonably, not in one place where decision-makers could be threatened or intimidated. If the Electoral College did not achieve a decisive majority, then the House of Representatives was to choose the president from among the top five candidates,[27] ensuring selection of a presiding officer administering the laws would have both ability and good character. Hamilton was also concerned about somebody unqualified, but with a talent for "low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity" attaining high office.[26]

Additionally, in the Federalist No. 10, James Madison argued against "an interested and overbearing majority" and the "mischiefs of faction" in an electoral system. He defined a faction as "a number of citizens whether amounting to a majority or minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community." What was then called republican government (i.e., representative democracy, as opposed to direct democracy) combined with the principles of federalism (with distribution of voter rights and separation of government powers) would countervail against factions. Madison further postulated in the Federalist No. 10 that the greater the population and expanse of the Republic, the more difficulty factions would face in organizing due to such issues as sectionalism.[28]

Although the United States Constitution refers to "Electors" and "electors", neither the phrase "Electoral College" nor any other name is used to describe the electors collectively. It was not until the early 19th century the name "Electoral College" came into general usage as the collective designation for the electors selected to cast votes for president and vice president. The phrase was first written into federal law in 1845 and today the term appears in 3 U.S.C. § 4, in the section heading and in the text as "college of electors".[29]

History

Initially, state legislatures chose the electors in many of the states. That practice changed during the early 19th century, as states extended the right to vote to wider segments of the population. By 1832, only South Carolina had not transitioned to popular election. Since 1880, the electors in every state have been chosen based on a popular election held on Election Day.[1] The popular election for electors means the president and vice president are in effect chosen through indirect election by the citizens.[30] Since the mid-19th century when all electors have been popularly chosen, the Electoral College has elected the candidate who received the most popular votes nationwide, except in four elections: 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016. In 1824, there were six states in which electors were legislatively appointed, rather than popularly elected, so the true national popular vote is uncertain; the electors failed to select a winning candidate, so the matter was decided by the House of Representatives.[31]Original plan

Article II, Section 1, Clause 3 of the Constitution provided the original plan by which the electors voted for president. Under the original plan, each elector cast two votes for president; electors did not vote for vice president. Whoever received a majority of votes from the electors would become president, with the person receiving the second most votes becoming vice president.The original plan of the Electoral College was based upon several assumptions and anticipations of the Framers of the Constitution:[32]

- Choice of the president should reflect the "sense of the people" at a particular time, not the dictates of a faction in a "pre-established body" such as Congress or the State legislatures, and independent of the influence of "foreign powers".[33]

- The choice would be made decisively with a "full and fair expression of the public will" but also maintaining "as little opportunity as possible to tumult and disorder".[34]

- Individual electors would be elected by citizens on a district-by-district basis. Voting for president would include the widest electorate allowed in each state.[35]

- Each presidential elector would exercise independent judgment when voting, deliberating with the most complete information available in a system that over time, tended to bring about a good administration of the laws passed by Congress.[33]

- Candidates would not pair together on the same ticket with assumed placements toward each office of president and vice president.

- The system as designed would rarely produce a winner, thus sending the presidential election to the House of Representatives.

Breakdown and revision

The emergence of political parties and nationally coordinated election campaigns soon complicated matters in the elections of 1796 and 1800. In 1796, Federalist Party candidate John Adams won the presidential election. Finishing in second place was Democratic-Republican Party candidate Thomas Jefferson, the Federalists' opponent, who became the vice president. This resulted in the president and vice president being of different political parties.In 1800, the Democratic-Republican Party again nominated Jefferson for president and also nominated Aaron Burr for vice president. After the electors voted, Jefferson and Burr tied one another with 73 electoral votes each. Since ballots did not distinguish between votes for president and votes for vice president, every ballot cast for Burr technically counted as a vote for him to become president, despite Jefferson clearly being his party's first choice. Lacking a clear winner by constitutional standards, the election had to be decided by the House of Representatives pursuant to the Constitution's contingency election provision.

Having already lost the presidential contest, Federalist Party representatives in the lame duck House session seized upon the opportunity to embarrass their opposition by attempting to elect Burr over Jefferson. The House deadlocked for 35 ballots as neither candidate received the necessary majority vote of the state delegations in the House (the votes of nine states were needed for a conclusive election). Jefferson achieved electoral victory on the 36th ballot, but only after Federalist Party leader Alexander Hamilton—who disfavored Burr's personal character more than Jefferson's policies—had made known his preference for Jefferson.

Responding to the problems from those elections, the Congress proposed on December 9, 1803, and three-fourths of the states ratified by June 15, 1804, the Twelfth Amendment. Starting with the 1804 election, the amendment requires electors cast separate ballots for president and vice president, replacing the system outlined in Article II, Section 1, Clause 3.

Evolution to the general ticket

Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution states:Alexander Hamilton described the Founding Fathers' view of how electors would be chosen:Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector.

They assumed this would take place district by district. That plan was carried out by many states until the 1880s. For example, in Massachusetts in 1820, the rule stated "the people shall vote by ballot, on which shall be designated who is voted for as an Elector for the district."[37] In other words, the people did not place the name of a candidate for a president on the ballot, instead they voted for their local elector, whom they trusted later to cast a responsible vote for president.A small number of persons, selected by their fellow-citizens from the general mass, will be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to such complicated [tasks].[36]

Some states reasoned that the favorite presidential candidate among the people in their state would have a much better chance if all of the electors selected by their state were sure to vote the same way—a "general ticket" of electors pledged to a party candidate.[38] So the slate of electors chosen by the state were no longer free agents, independent thinkers, or deliberative representatives. They became "voluntary party lackeys and intellectual non-entities."[39] Once one state took that strategy, the others felt compelled to follow suit in order to compete for the strongest influence on the election.[38]

When James Madison and Hamilton, two of the most important architects of the Electoral College, saw this strategy being taken by some states, they protested strongly. Madison and Hamilton both made it clear this approach violated the spirit of the Constitution. According to Hamilton, the selection of the president should be "made by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station [of president]."[36] According to Hamilton, the electors were to analyze the list of potential presidents and select the best one. He also used the term "deliberate". Hamilton considered a pre-pledged elector to violate the spirit of Article II of the Constitution insofar as such electors could make no "analysis" or "deliberate" concerning the candidates. Madison agreed entirely, saying that when the Constitution was written, all of its authors assumed individual electors would be elected in their districts and it was inconceivable a "general ticket" of electors dictated by a state would supplant the concept. Madison wrote to George Hay:

The Founding Fathers assumed that each elector would be elected by the citizens of a district and that elector was to be free to analyze and deliberate regarding who is best suited to be president.The district mode was mostly, if not exclusively in view when the Constitution was framed and adopted; & was exchanged for the general ticket [many years later].[40]

Each state government was free to have its own plan for selecting its electors, and the Constitution does not explicitly require states to popularly elect their electors. Several methods for selecting electors are described below.

Madison and Hamilton were so upset by what they saw as a distortion of the original intent that they advocated a constitutional amendment to prevent anything other than the district plan: "the election of Presidential Electors by districts, is an amendment very proper to be brought forward," Madison told George Hay in 1823.[40] Hamilton went further. He actually drafted an amendment to the Constitution mandating the district plan for selecting electors.[41] However, Hamilton's untimely death in 1804 prevented him from advancing his proposed reforms any further.

Evolution of selection plans

In 1789, at-large popular vote, the winner-take-all method, began with Pennsylvania and Maryland; Massachusetts, Virginia and Delaware used a district plan by popular vote, and state legislatures chose in the five other states participating in the election (Connecticut, Georgia, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and South Carolina).[42] New York, North Carolina and Rhode Island did not participate in the election. New York's legislature deadlocked and abstained; North Carolina and Rhode Island had not yet ratified the Constitution.[43]By 1800, Virginia and Rhode Island voted at-large, Kentucky, Maryland, and North Carolina voted popularly by district, and eleven states voted by state legislature. Beginning in 1804 there was a definite trend towards the winner-take-all system for statewide popular vote.[44]

By 1832, only South Carolina legislatively chose its electors, and it abandoned the method after 1860.[44] Maryland was the only state using a district plan and from 1836 district plans fell out of use until the 20th century, though Michigan used a district plan for 1892 only. States using popular vote by district have included ten states from all regions of the country.[45]

Since 1836, statewide winner-take-all popular voting for electors has been the almost universal practice.[46] Currently, Maine (since 1972) and Nebraska (since 1996) use the district plan, with two at-large electors assigned to support the winner of the statewide popular vote.[47]

Three-fifths clause and the role of slavery

After the initial estimates agreed to in the original Constitution, Congressional and Electoral College reapportionment was made according to a decennial census to reflect population changes, modified by counting three-fifths of persons held as slaves for apportionment of representation. Beginning with the first census, Electoral College votes repeatedly eclipsed the electoral basis supporting slave-power in the choice of the U.S. president.[clarification needed][48][failed verification]At the Constitutional Convention, the Electoral College was authorized by a majority of 49 votes for northern states in the process of abolishing slavery, and 42 votes for slave-holding states (including Delaware). In the event, the first 1788 presidential election did not include Electoral College votes for unratified Rhode Island (3) and North Carolina (7), nor for New York (8) which reported too late; the Northern majority was 38 to 35.[49] For the next two decades of census apportionment in the Electoral College the Three-fifths clause awarded free-soil Northern states narrow majorities of 8% and 11% as the Southern states in Convention had given up two-fifths of their slave population in their federal apportionment compromise, but thereafter, Northern states assumed uninterrupted majorities with margins ranging from 15.4% to 23.2%.[50]

While Southern state Congressional delegations were boosted by an average of one-third during each decade of this period,[51] the margin of free-soil Electoral College majorities were still maintained over this entire early republic and antebellum period.[52] Scholars further conclude that the Three-fifths clause had limited impact on sectional proportions in party voting and factional strength. The seats that the South gained from a slave bonus were evenly distributed between the parties of the period. At the First Party System (1795–1823), the Jefferson Republicans gained 1.1 percent more adherents from the slave bonus, while the Federalists lost the same proportion. At the Second Party System (1823–1837) the emerging Jacksonians gained just 0.7% more seats, versus the opposition loss of 1.6%.[53]

The Three-fifths rule of apportionment in the Electoral College eventually resulted in three counter-factual losses in the sixty-eight years from 1792–1860. With that clause, the slaveholding states gave up two-fifths of their slave population in federal apportionment, giving a margin of victory to John Adams in his 1796 election defeating Thomas Jefferson.[54] Then in 1800, historian Garry Wills argues, Jefferson's victory over Adams was due to the slave bonus count in the Electoral College because Adams would have won if only popular votes cast counted.[55] However, historian Sean Wilentz points out that Jefferson's purported "slave advantage" ignores an offset by electoral manipulation by anti-Jefferson forces in Pennsylvania. Wilentz concludes that it is a myth to say that the Electoral College was a pro-slavery ploy.[56]

In 1824, the presidential selection was thrown into the House of Representatives, and John Quincy Adams was chosen over Andrew Jackson, even though Jackson had a larger popular vote plurality. Then Andrew Jackson won in 1828, but that second campaign would also have been lost if the count in the Electoral College were by citizen-only apportionment alone. Scholars conclude that in the 1828 race, Jackson benefited materially from the Three-fifths clause by providing his margin of victory. The impact of the Three-fifths clause in both Jefferson's first and Jackson's first presidential elections was significant because each of them launched sustained Congressional party majorities over several Congresses, as well as presidential party eras.[57]

Besides the Constitutional slavery provisions prohibiting Congress from regulating foreign or domestic slave trade before 1808, and a positive requirement for states to return escaped "persons held to service",[58] legal scholar Akhil Reed Amar argues that the Electoral College was originally advocated by slave-holders in an additional effort to defend slavery. In the Congressional apportionment provided in the text of the Constitution with its Three-Fifths Compromise estimate, "Virginia emerged as the big winner [with] more than a quarter of the [votes] needed to win an election in the first round [for Washington's first presidential election in 1788]." Following the 1790 census, the most populous state in the 1790 Census was Virginia, a slave state with 39.1% slaves, or 292,315 counted three-fifths, to yield a calculated number of 175,389 for congressional apportionment.[59] "The 'free' state of Pennsylvania had 10% more free persons than Virginia, but got 20% fewer electoral votes."[60] Pennsylvania split eight to seven for Jefferson, favoring Jefferson with a majority of 53% in a state with 0.1% slave population.[61] Historian Eric Foner agrees that the Constitution's Three-Fifths Compromise gave protection to slavery.[62]

Supporters of the Electoral College have provided many counterarguments to the charges that it defended slavery. Abraham Lincoln, the president who helped abolish slavery, won an Electoral College majority in 1860 despite winning less than 40 percent of the national popular vote.[63] Lincoln's 39.8%, however, represented a plurality of a popular vote that was divided among four major candidates.

Dave Benner argues that although the additional population of slave states from the Three-Fifths Compromise allowed Jefferson to defeat Adams in 1800, Jefferson's margin of victory would have been wider had the entire slave population been counted.[64] He also notes that some of the most vociferous critics of a national popular vote at the constitutional convention were delegates from free states, including Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania, who declared that such a system would lead to a "great evil of cabal and corruption," and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, who called a national popular vote "radically vicious".[64] Delegates Oliver Ellsworth and Roger Sherman of Connecticut, a state which had adopted a gradual emancipation law three years earlier, also criticized the use of a national popular vote system.[64] Likewise, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, a member of Adams' Federalist Party and himself a presidential candidate in 1800, hailed from South Carolina and was himself a slaveowner.[64] In 1824, Andrew Jackson, a slaveowner from Tennessee, was similarly defeated by John Quincy Adams, an outspoken critic of slavery.[64]

Fourteenth Amendment

Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment allows for a state's representation in the House of Representatives to be reduced if a state unconstitutionally denies people the right to vote. The reduction is in keeping with the proportion of people denied a vote. This amendment refers to "the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice President of the United States" among other elections, the only place in the Constitution mentioning electors being selected by popular vote.On May 8, 1866, during a debate on the Fourteenth Amendment, Thaddeus Stevens, the leader of the Republicans in the House of Representatives, delivered a speech on the amendment's intent. Regarding Section 2, he said:[65]

Federal law (2 U.S.C. § 6) implements Section 2's mandate.The second section I consider the most important in the article. It fixes the basis of representation in Congress. If any State shall exclude any of her adult male citizens from the elective franchise, or abridge that right, she shall forfeit her right to representation in the same proportion. The effect of this provision will be either to compel the States to grant universal suffrage or so shear them of their power as to keep them forever in a hopeless minority in the national Government, both legislative and executive.[66]

Meeting of electors

Article II, Section 1, Clause 4 of the Constitution states:Since 1936, federal law has provided that the electors in all the states (and, since 1964, in the District of Columbia) meet "on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December next following their appointment" to vote for president and vice president.[67][68]The Congress may determine the Time of chusing [sic] the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States.

Under Article II, Section 1, Clause 2, all elected and appointed federal officials are prohibited from being electors. The Office of the Federal Register is charged with administering the Electoral College.[69]

After the vote, each state then sends a certified record of their electoral votes to Congress. The votes of the electors are opened during a joint session of Congress, held in the first week of January, and read aloud by the incumbent vice president, acting in his capacity as President of the Senate. If any person received an absolute majority of electoral votes that person is declared the winner.[70] If there is a tie, or if no candidate for either or both offices receives a majority, then choice falls to Congress in a procedure known as a contingent election.

MORE HERE: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Electoral_College

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo