Human consciousness and the 'twilight zone' of awareness

New research shows what's happening in the brain when conscious awareness fades.

Since temps immémorial, the question, "How does human consciousness work?" has intrigued philosophers, poets, playwrights, anaesthesiologists, brain scientists, songwriters, and people from all walks of life who are inclined to think about their thinking.

William Shakespeare's writings and Gary Wright's "Dream Weaver" lyrics from the mid-1970s, quoted below, are famous cultural references that exemplify various ways humans throughout the ages have sought to describe how our states of consciousness vacillate between wakefulness and sleep.

"Fast asleep? It is no matter; Enjoy the honey-heavy dew of slumber: Thou hast no figures nor no fantasies, Which busy care draws in the brains of men; Therefore thou sleep'st so sound." —William Shakespeare (Julius Caesar, c. 1599)

"Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed, the dear repose for limbs with travel tired. But then begins a journey in my head, to work my mind, when body's work's expired: For then my thoughts (from far where I abide) Intend a zealous pilgrimage to thee." —William Shakespeare (Sonnet XXVII, c. 1609)

"I've just closed my eyes again and climbed aboard the dream weaver train. Take away my worries of today and leave tomorrow behind. Fly me high through the starry skies, maybe to an astral plane. Cross the highways of fantasy and help me forget today's pain." —Gary Wright ("Dream Weaver," c. 1975)

Source: agsandrew/Shutterstock

For centuries, the brain mechanisms that support conscious awareness during wakefulness or a lack of consciousness during sleep (or when someone is under general anesthesia) have confounded neuroscientists. Despite 21st-century advances in scientific research, the neural correlates of human consciousness remain surprisingly mysterious.

In a 2012 New York Times article, "Awake or Knocked Out? The Line Gets Blurrier," James Gorman wrote, "The puzzle of consciousness is so devilish that scientists and philosophers are still struggling with how to talk about it, let alone figure out what it is and where it comes from."

In this NYT piece, Gorman references a Science paper (Alkire, Hudetz, & Tononi, 2008) in which the authors write, "When we are anesthetized, we expect consciousness to vanish. But does it always? Although anesthesia undoubtedly induces unresponsiveness and amnesia, the extent to which it causes unconsciousness is harder to establish."

Gorman also cites a study (Långsjö et al., 2012)—led by Harry Scheinen and Jaakko Långsjö of Finland's University of Turku and published in The Journal of Neuroscience—which found that when someone "returns from oblivion" after receiving an anesthetic agent, the emergence of consciousness is "associated with the activation of a core network involving subcortical and limbic regions that become functionally coupled with parts of frontal and inferior parietal cortices upon awakening from unconsciousness."

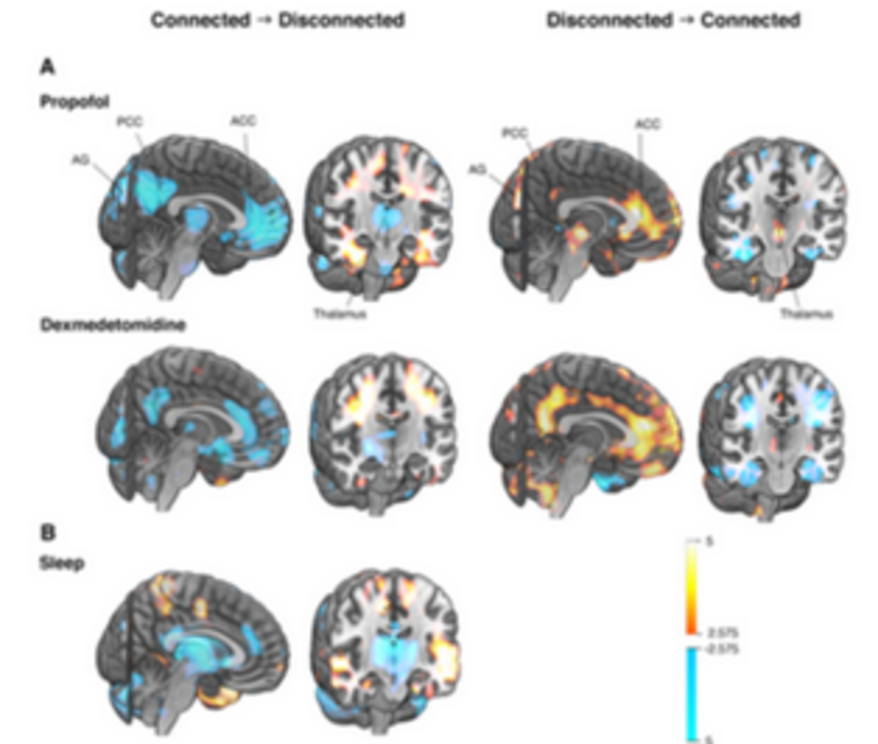

Differences in brain activity between connected and disconnected states of consciousness studied with positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. Activity of the thalamus, anterior (ACC) and posterior cingulate cortices (PCC), and bilateral angular gyri (AG) show the most consistent associations with the state of consciousness (A = general anesthesia, B = sleep). Source: Scheinin et al., JNeurosci 2020, labeled for reuse.

Now, almost a decade later, a new PET scan study, "Foundations of Human Consciousness: Imaging the Twilight Zone," from the University of Turku led by Harry Scheinen gives us more state-of-the-art insights related to "what happens in the brain when conscious awareness of the surrounding world fades." These findings (Scheinin et al., 2020) were published on December 28 in The Journal of Neuroscience.

For this study, the Finnish researchers focused on disconnected and connected states of consciousness. "Disconnected states of consciousness were defined as unresponsive anesthesia states and non-REM sleep phases, with subsequent reports of no indication of the subject's connection to the outside world," the researchers explain in a news release.

"Trying to understand the biological basis of human consciousness is currently one of the greatest challenges of neuroscience," the authors write in the paper's significance statement. "Here, we present carefully designed studies that overcome many previous confounders and for the first time reveal the neural mechanisms underlying human consciousness and its disconnection from behavioral responsiveness, both during anesthesia and during normal sleep. [Our] findings identify a central core brain network critical for human consciousness."

In a cohort of roughly four dozen study subjects, the researchers monitored functional brain activity along with various states of consciousness during two randomized experiments. The first experiment used anesthetic agents to achieve a disconnected state in which the test subject showed no signs of awareness related to the surrounding world. For the second experiment, study participants were encouraged to doze off in the lab naturally, without any pharmacologic agents.

Halfway through both experiments, subjects were jolted awake from their disconnected state by the researchers. Moments after waking up, the researchers began conducting interviews designed to elicit detailed descriptions of each person's subjective experiences during the preceding period of unresponsiveness.

Interestingly, the researchers found that someone's degree of responsiveness doesn't necessarily reflect their state of consciousness. For example, a seemingly unresponsive person might still be in a connected state and aware of their surroundings. "Unresponsiveness rarely denoted unconsciousness, as the majority of the subjects had internally generated experiences," the authors observed. These findings corroborate earlier findings by Turku researchers, which found that anesthesia doesn't always shut down consciousness completely.

Accumulating evidence related to anesthesia mechanisms from the Turku PET Centre sheds light on the neural basis of human consciousness. Their most recent research advances our understanding of how the brain functions in the so-called "twilight zone" between waking consciousness and complete unresponsiveness marked by someone not having any awareness of the surrounding world.

"Due to the short delay between awakenings and interviews, the new [2020] results significantly increase our understanding of the nature of anesthesia," first author Annalotta Scheinin said in a news release. "Contrary to popular belief, successful general anesthesia, therefore, does not require complete loss of consciousness. It is enough that we detach the patient's experiences from what is happening in the outside world (i.e., the operating room)."

"Changes in connectedness corresponded to the activity of a network comprised of regions deep inside the brain: the thalamus, anterior and posterior cingulate cortex, and angular gyri," the authors note. "These regions exhibited less blood flow when a participant lost connectedness and more blood flow when they regained it." Based on their latest findings, Scheinin et al. conclude, "activity of the thalamus, cingulate cortices, and angular gyri are fundamental for human consciousness."

https://nexusnewsfeed.com/article/consciousness/human-consciousness-and-the-twilight-zone-of-awareness

Thanks to: https://nexusnewsfeed.com

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo