Blasting the Ocean with Noise: how Sonic Pollution and Sea Mining will destroy Marine Life

We could make it stop, so why don’t we?

By David George Haskell on 28th Nov 2022. on Stigmatis/ Mining Illustrations added. via thefreeonline

The fuzz and beep of ship radios stitched a net over the water, a blurry facsimile of the sonic connections of the whales themselves. Every skipper heard the voices of the others, relayed by electromagnetic waves.

The quarry could not escape. “Whales guaranteed” shouted the billboards on shore.

We motored on, weaving around island headlands. A sighting off the south-west shore of San Juan Island. Through binoculars: a dorsal fin scythed the water, then dipped.

https://youtu.be/befIlWZ2T_U

The SUNRISE Project – the dawning of sound science of the deep

Another, with a spray of mist as the animal exhaled. Then, no sign. But the whales’ location was easy to spot. A dozen boats clustered, most slowly motoring west, away from the shore. We powered closer, slowing the engine until we were travelling without raising a wake and took our place on the outer edge of the gaggle of yachts and cruisers.

A sheet of marble skated just under the water’s surface. Oily smooth. A spill of black ink sheeting under the hazed bottle glass of the water’s surface. Praaf! Surfacing 15 metres ahead of the boat, the exhalation was plosive and rough.

The pod of about 10 animals came to the surface. Part of the L pod of orcas, our captain said, one of three pods that form the “southern residents” in the waters of the Salish Sea between Seattle and Vancouver, often seen hunting salmon around the San Juan Islands. Others – “transients” that ply coastal waters and “offshores” that feed mostly in the Pacific – also visit regularly.

The L pod continued west, heading toward the Haro Strait. Our engines purred as the U-shaped arc of boats tracked the pod, leaving open water ahead of the whales.

False choice’ – is deep sea mining required for an electric vehicle revolution?

Read more

Read more

https://youtu.be/rwlcUsenpS4

We dropped a hydrophone over the boat’s gunwale, its cord feeding a small speaker in a plastic casing. Whale sounds! And engine noise, lots of engine noise. Clicks, like taps on a metal can, came in squalls. These sounds are the whales’ echolocating search beams. The whales use the echoes not only to see through the murky water, but to understand how soft, taut, fast or tremulous matter is around them.

Mixed with the staccato of the whales’ clicks were whistles and high squeaks, sounds that undulate, dart, inflect up and spiral down. These whistles are the sounds of whale conviviality, given most often when the animals are socialising at close range.

When the pod is more widely spaced during searches for food, the whales whistle less and communicate with bursts of shorter sound pulses. These sonic bonds not only connect the members of each pod, but distinguish the pod from others.

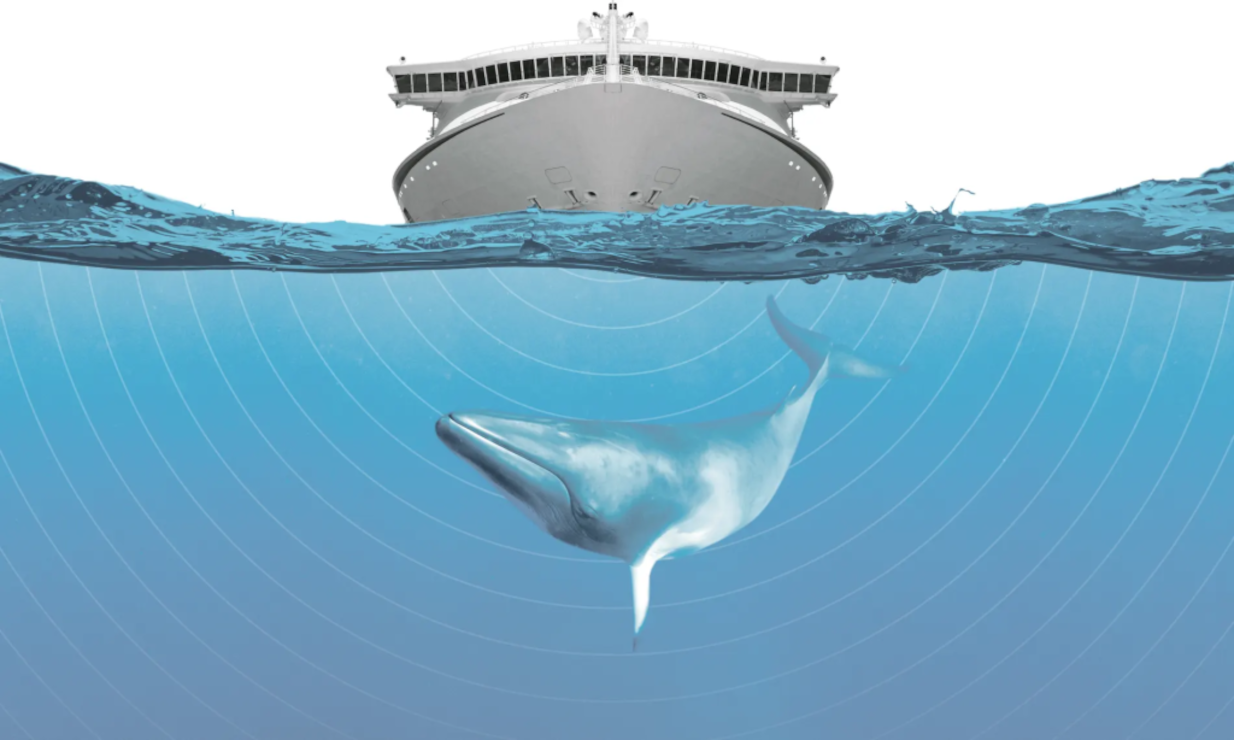

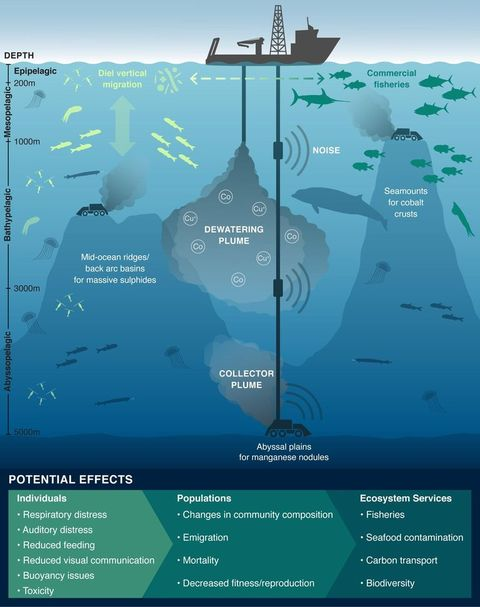

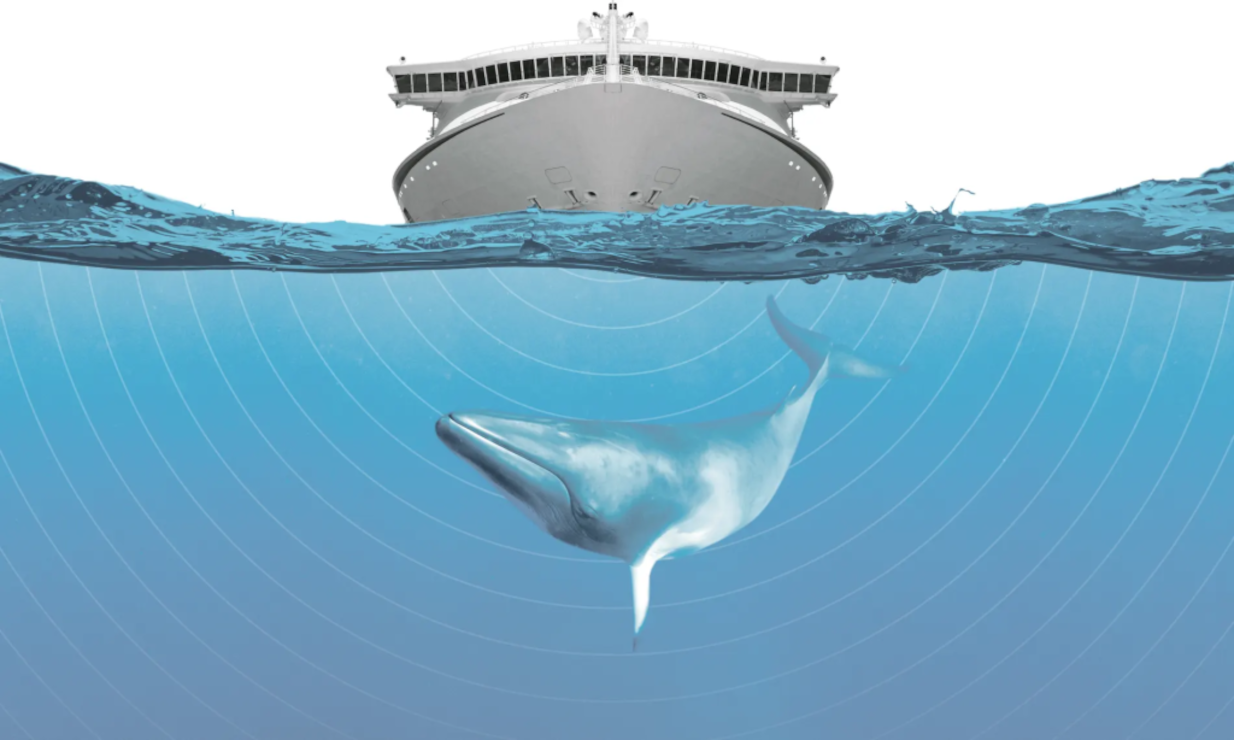

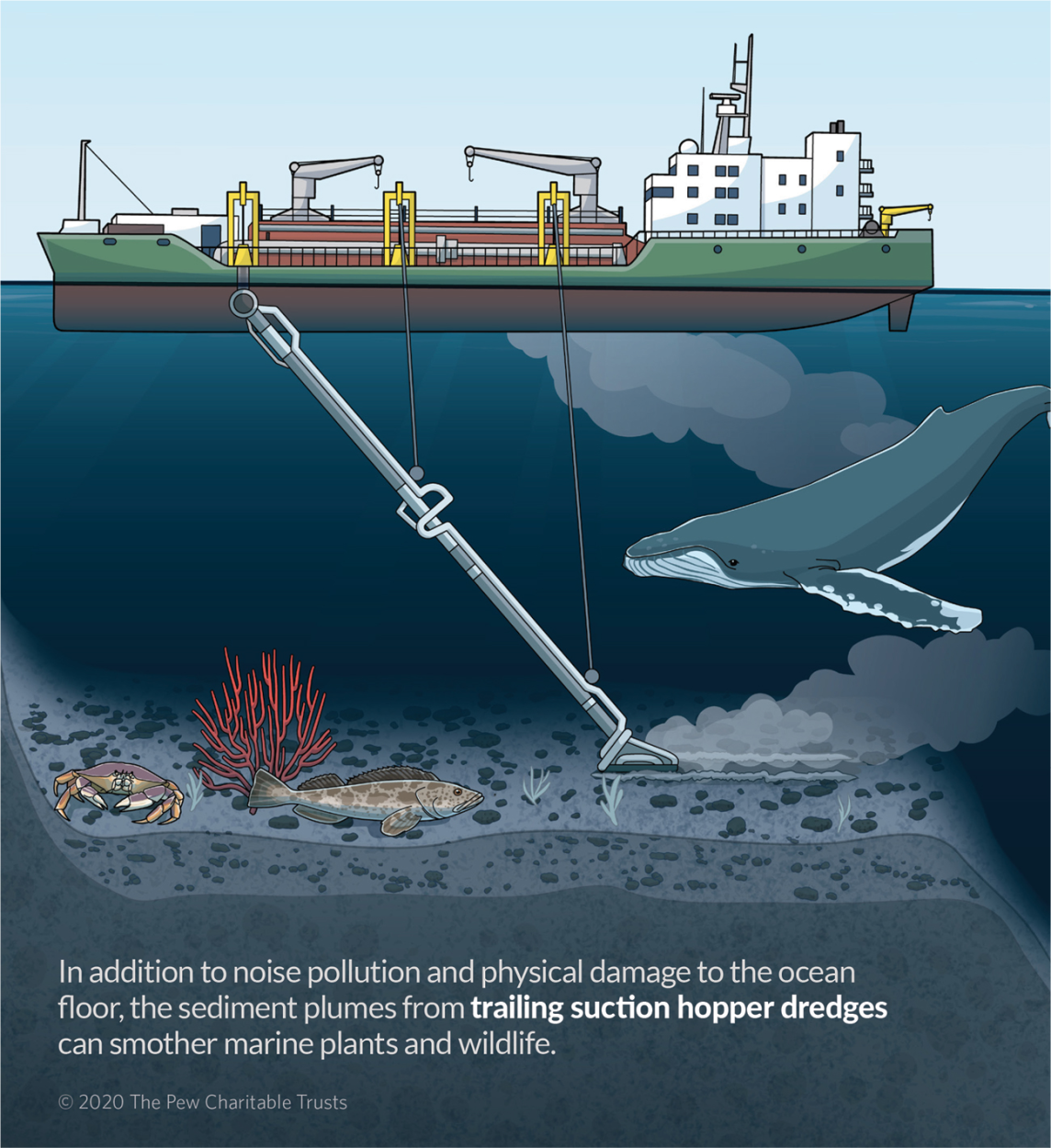

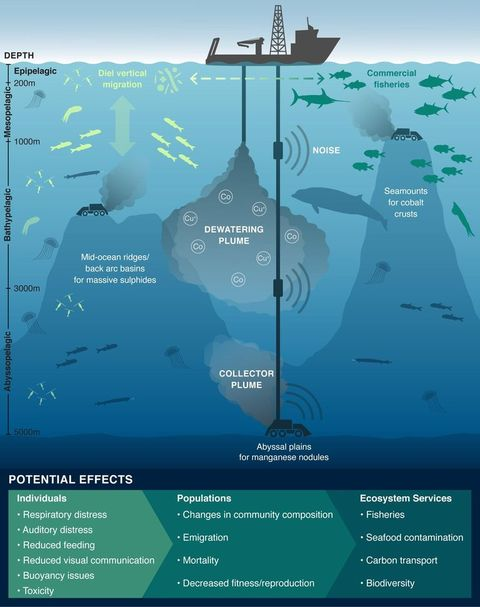

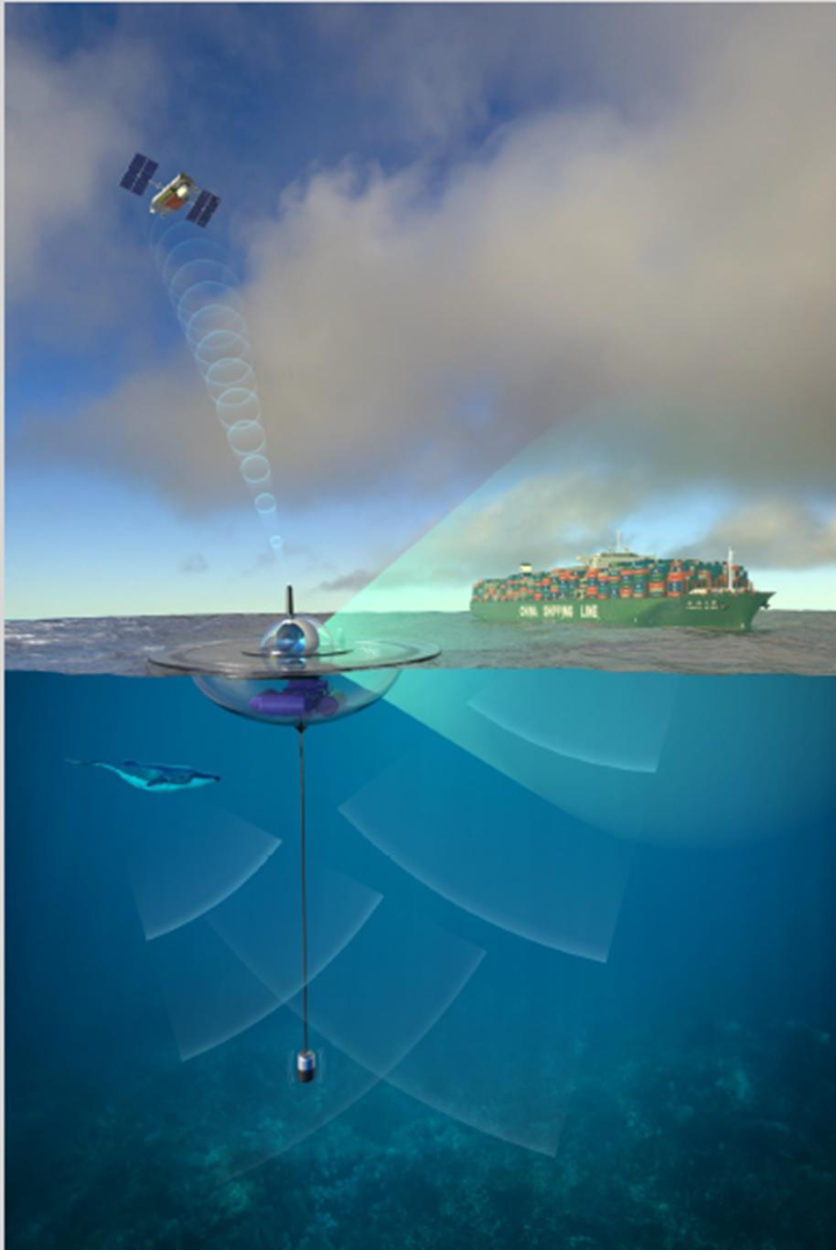

Today, ocean waters are a tumult of engine noise, sonar and seismic blasts. Sediments from human activities on land cloud the water. Industrial chemicals befuddle the sense of smell of aquatic animals. We are severing the sensory links that gave the world its animal diversity.

Whales cannot hear the echolocating pulses that locate their prey, breeding fish cannot find one another amid the noise and turbidity, and the social connections among crustaceans are weakened as their chemical messages and sonic thrums are lost in a haze of human pollution.

see also. New Threat to Life: The Internet of Underwater Things- WEF mandate for Stakeholders Ocean ProfitabilityFebruary 15, 2022

Here off the coast of San Juan Island, the whales’ voices were like fine silk stitched into a thick denim of propeller and motor sound, clicks and whistles sometimes audible but often disappearing into the tight weave of engines. The dozen boats gave off throbs, whirs and shudders as they tracked the whales, combustion engines swaddling the whales in an inescapable, constricting wrap.

In the distance, I could see a container ship and an oil tanker headed north through the Haro Strait, likely bound for Vancouver, the largest port in the region – two of the more than 7,000 large vessels that, combined, make more than 12,000 transits through the strait every year.

These range from bulk carriers to container ships to tankers, many of which are 200 or 300 metres long. Large vessels also ply the waters west of the Haro Strait, headed to ports and refineries in and around Seattle and Tacoma. Each one of these vessels makes sound audible underwater from tens, sometimes hundreds, of miles.

Unlike small pleasure boats that are usually moored at sundown, these large vessels make noise all night and day, and are often most active and loudest at night. The largest container ships blast at about 190 underwater decibels or more, the equivalent on land of a thunderclap or the takeoff of a jet.

The southern resident whale community whose life centres on these waters cannot bear the noise. Their population is in decline, likely headed to extinction unless the world gets more hospitable. In the 1990s, the community numbered in the 90s.

Now they’ve dropped to the [url=https://www.mmc.gov/priority-topics/species-of-concern/southern-resident-killer-whale/#:~:text=The total abundance for the,stands at only 74 whales.]low 70s[/url], losing one or two more animals every year without raising new calves. In 2005, they were listed under the US Endangered Species Act. No single factor is responsible, but the interaction of shipping sounds, dwindling food supply and chemical pollution is, for now, closing the door on their future.

These whales are the falcons of the ocean, rocketing down 100 metres or more in pursuit of their nimble and speedy prey, the chinook salmon. Sound frequencies of boat noise overlap with the clicks that the animals use to echolocate and find their prey. Noise raises a fog, blinding the hunters. If a whale is within 200 metres of a container ship or 100 metres of a smaller boat with an outboard engine, its echolocation range is reduced by 95%.

New Threat to Life: The Internet of Underwater Thing

In air, we hear only a low groan from passing vessels. The sound is mostly transmitted down, below the waves, and the aerial portion is quickly dissipated. Under the surface, the sonic violence of powered boats travels fast and far through the pulse and heave of water molecules. These movements flow directly into aquatic living beings. Sound in air mostly bounces off terrestrial animals, reflected back by the uncooperative border of air to skin.

Our middle-ear bones and eardrum are specifically designed to overcome this barrier, gathering aerial sound and delivering it to the aquatic medium of the inner ear. Sound, for us, is focused mostly on a few organs in our heads.

But aquatic animals are immersed in sound. Sound flows almost unimpeded from watery surrounds to watery innards. “Hearing” is a full-body experience.

For most whales, and for many fish and invertebrate animals, eyes are only occasionally useful. In the abyssal depths, the animals swim in ink. Along coasts, the water is so turbid that animals see, at most, a body length ahead. Sound reveals the shapes, energies, boundaries and other inhabitants of the sea. Sound is also a communicative bond. In the ocean, as is true in the rainforest where dense foliage occludes vision, sound connects you to unseen mates, kin and rivals, and it alerts you to nearby prey and predators.

If salmon were abundant, all this noise might not be a problem. But the chinook salmon that compose most of the whales’ diet here are in crisis. Dams, urbanisation, agriculture and logging have cut off or degraded most of the freshwater rivers and streams in which the fish spawn and live out their first months.

Chinook salmon numbers in this region have declined by 60% since the 1980s, and possibly more than 90% since the early 20th century. Under current conditions, models forecast, at best, a fragile southern resident population. Any additional stress will send them to extinction.

A humpback whale and her calf. Photograph: lindsay_imagery/Getty

CONTINUE HERE: https://thefreeonline.com/2022/11/29/blasting-the-ocean-with-noise-how-sonic-pollution-and-sea-mining-will-destroy-marine-life/

We could make it stop, so why don’t we?

By David George Haskell on 28th Nov 2022. on Stigmatis/ Mining Illustrations added. via thefreeonline

An ocean of noise: how sonic pollution is hurting marine life – podcast listen here..

We were whaling with cameras, joining a flotilla of a dozen other tourist boats from harbours all around the Salish Sea. It was one of my first trips to the area, in August 2001.The fuzz and beep of ship radios stitched a net over the water, a blurry facsimile of the sonic connections of the whales themselves. Every skipper heard the voices of the others, relayed by electromagnetic waves.

The quarry could not escape. “Whales guaranteed” shouted the billboards on shore.

We motored on, weaving around island headlands. A sighting off the south-west shore of San Juan Island. Through binoculars: a dorsal fin scythed the water, then dipped.

https://youtu.be/befIlWZ2T_U

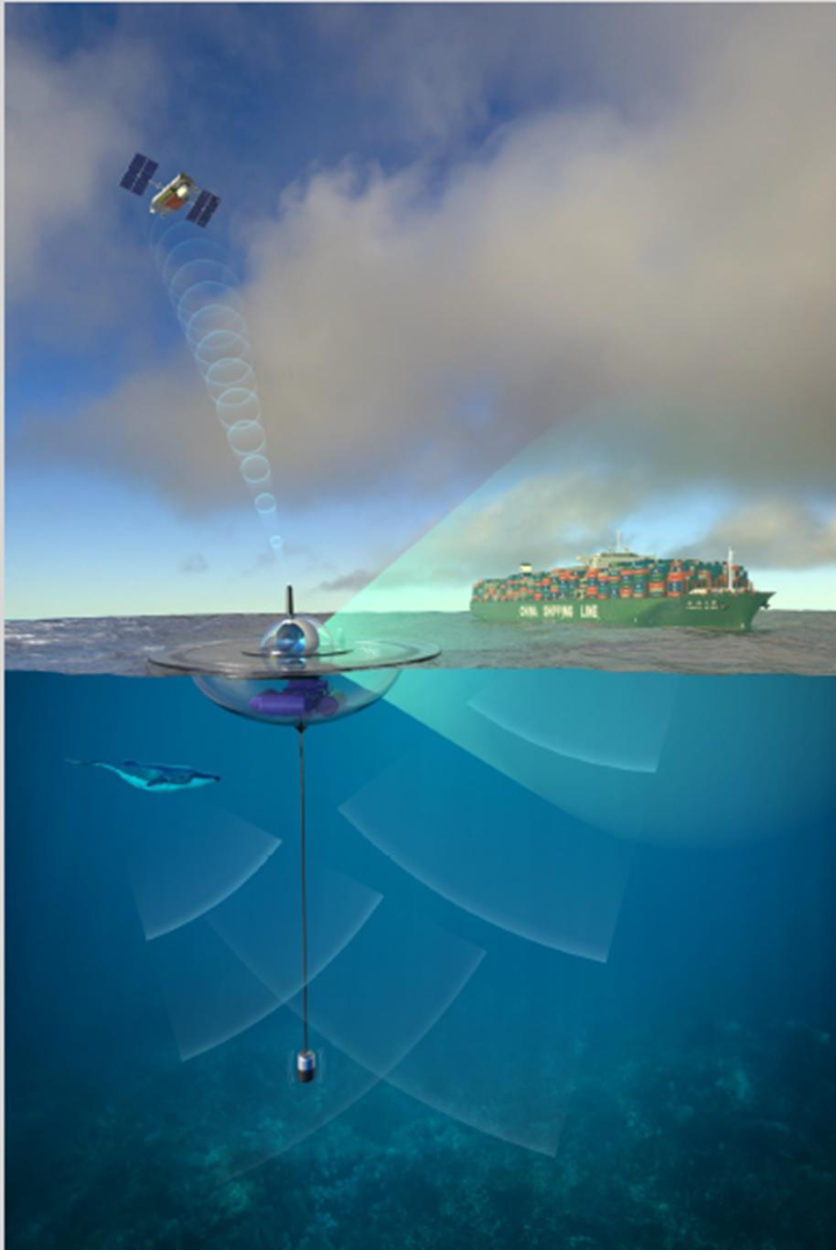

The SUNRISE Project – the dawning of sound science of the deep

Another, with a spray of mist as the animal exhaled. Then, no sign. But the whales’ location was easy to spot. A dozen boats clustered, most slowly motoring west, away from the shore. We powered closer, slowing the engine until we were travelling without raising a wake and took our place on the outer edge of the gaggle of yachts and cruisers.

A sheet of marble skated just under the water’s surface. Oily smooth. A spill of black ink sheeting under the hazed bottle glass of the water’s surface. Praaf! Surfacing 15 metres ahead of the boat, the exhalation was plosive and rough.

The pod of about 10 animals came to the surface. Part of the L pod of orcas, our captain said, one of three pods that form the “southern residents” in the waters of the Salish Sea between Seattle and Vancouver, often seen hunting salmon around the San Juan Islands. Others – “transients” that ply coastal waters and “offshores” that feed mostly in the Pacific – also visit regularly.

The L pod continued west, heading toward the Haro Strait. Our engines purred as the U-shaped arc of boats tracked the pod, leaving open water ahead of the whales.

False choice’ – is deep sea mining required for an electric vehicle revolution?

Seismic & Sonar Testing

While whales and other marine life are threatened by international whaling and habitat loss, they also face a domestic threat. Navy sonar testing and seismic testing from the oil and gas industry regularly take place in areas where marine species thrive. Find out more about the impacts and what you can do to help...”Read more

What Is Ocean Noise Pollution, and How Does It Disrupt Marine Life?

Over 1,000 whales died when they became trapped in the ice. Navy sonar and seismic blasts affect numerous marine species, including beaked whales. When the high-decibel sounds spook the whales, they alter their dive patterns, and some die from decompression sickness when surfacing.Read more

https://youtu.be/rwlcUsenpS4

We dropped a hydrophone over the boat’s gunwale, its cord feeding a small speaker in a plastic casing. Whale sounds! And engine noise, lots of engine noise. Clicks, like taps on a metal can, came in squalls. These sounds are the whales’ echolocating search beams. The whales use the echoes not only to see through the murky water, but to understand how soft, taut, fast or tremulous matter is around them.

Mixed with the staccato of the whales’ clicks were whistles and high squeaks, sounds that undulate, dart, inflect up and spiral down. These whistles are the sounds of whale conviviality, given most often when the animals are socialising at close range.

When the pod is more widely spaced during searches for food, the whales whistle less and communicate with bursts of shorter sound pulses. These sonic bonds not only connect the members of each pod, but distinguish the pod from others.

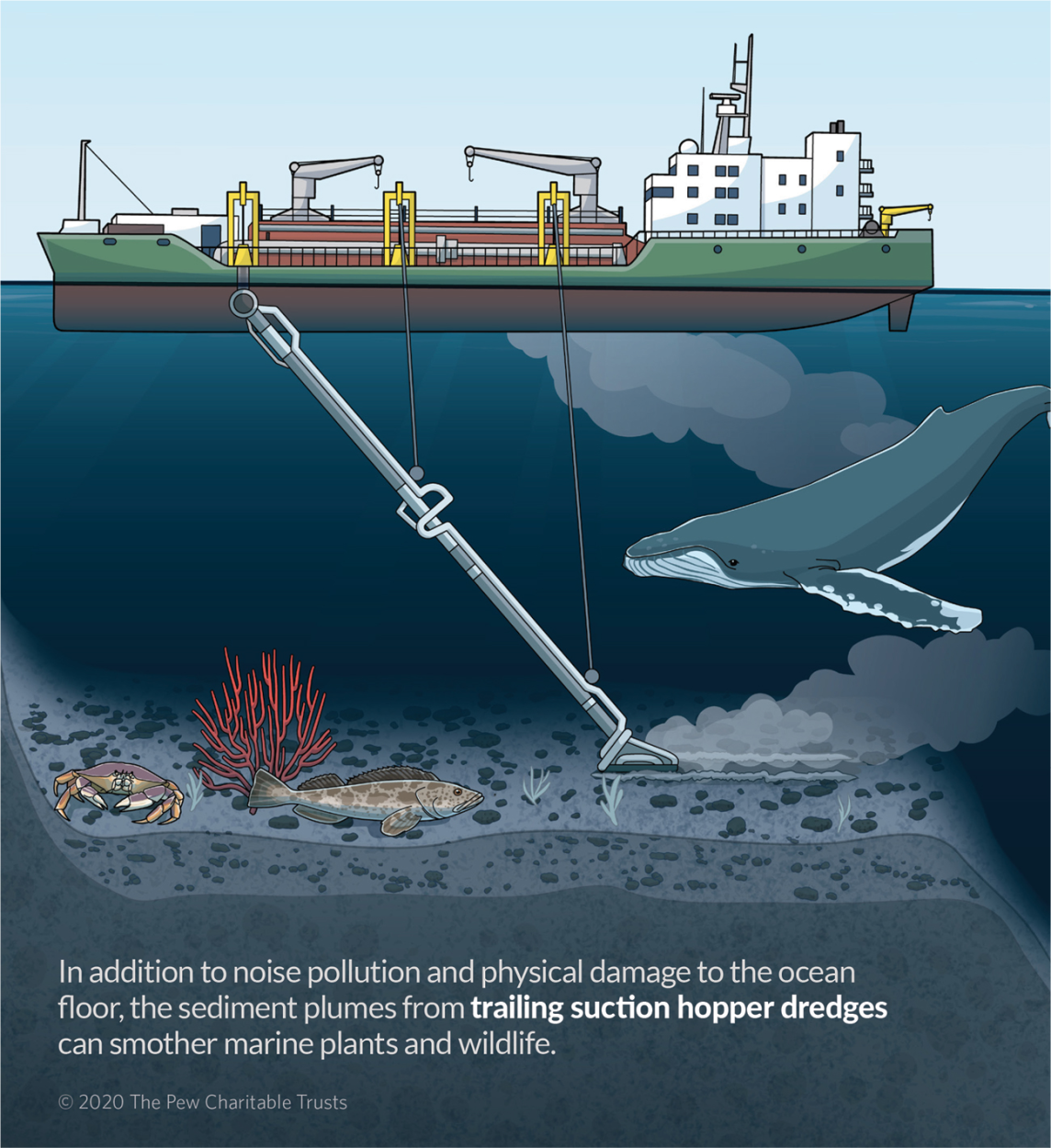

Today, ocean waters are a tumult of engine noise, sonar and seismic blasts. Sediments from human activities on land cloud the water. Industrial chemicals befuddle the sense of smell of aquatic animals. We are severing the sensory links that gave the world its animal diversity.

Whales cannot hear the echolocating pulses that locate their prey, breeding fish cannot find one another amid the noise and turbidity, and the social connections among crustaceans are weakened as their chemical messages and sonic thrums are lost in a haze of human pollution.

see also. New Threat to Life: The Internet of Underwater Things- WEF mandate for Stakeholders Ocean ProfitabilityFebruary 15, 2022

Here off the coast of San Juan Island, the whales’ voices were like fine silk stitched into a thick denim of propeller and motor sound, clicks and whistles sometimes audible but often disappearing into the tight weave of engines. The dozen boats gave off throbs, whirs and shudders as they tracked the whales, combustion engines swaddling the whales in an inescapable, constricting wrap.

In the distance, I could see a container ship and an oil tanker headed north through the Haro Strait, likely bound for Vancouver, the largest port in the region – two of the more than 7,000 large vessels that, combined, make more than 12,000 transits through the strait every year.

These range from bulk carriers to container ships to tankers, many of which are 200 or 300 metres long. Large vessels also ply the waters west of the Haro Strait, headed to ports and refineries in and around Seattle and Tacoma. Each one of these vessels makes sound audible underwater from tens, sometimes hundreds, of miles.

Unlike small pleasure boats that are usually moored at sundown, these large vessels make noise all night and day, and are often most active and loudest at night. The largest container ships blast at about 190 underwater decibels or more, the equivalent on land of a thunderclap or the takeoff of a jet.

The southern resident whale community whose life centres on these waters cannot bear the noise. Their population is in decline, likely headed to extinction unless the world gets more hospitable. In the 1990s, the community numbered in the 90s.

Now they’ve dropped to the [url=https://www.mmc.gov/priority-topics/species-of-concern/southern-resident-killer-whale/#:~:text=The total abundance for the,stands at only 74 whales.]low 70s[/url], losing one or two more animals every year without raising new calves. In 2005, they were listed under the US Endangered Species Act. No single factor is responsible, but the interaction of shipping sounds, dwindling food supply and chemical pollution is, for now, closing the door on their future.

These whales are the falcons of the ocean, rocketing down 100 metres or more in pursuit of their nimble and speedy prey, the chinook salmon. Sound frequencies of boat noise overlap with the clicks that the animals use to echolocate and find their prey. Noise raises a fog, blinding the hunters. If a whale is within 200 metres of a container ship or 100 metres of a smaller boat with an outboard engine, its echolocation range is reduced by 95%.

New Threat to Life: The Internet of Underwater Thing

In air, we hear only a low groan from passing vessels. The sound is mostly transmitted down, below the waves, and the aerial portion is quickly dissipated. Under the surface, the sonic violence of powered boats travels fast and far through the pulse and heave of water molecules. These movements flow directly into aquatic living beings. Sound in air mostly bounces off terrestrial animals, reflected back by the uncooperative border of air to skin.

Our middle-ear bones and eardrum are specifically designed to overcome this barrier, gathering aerial sound and delivering it to the aquatic medium of the inner ear. Sound, for us, is focused mostly on a few organs in our heads.

But aquatic animals are immersed in sound. Sound flows almost unimpeded from watery surrounds to watery innards. “Hearing” is a full-body experience.

For most whales, and for many fish and invertebrate animals, eyes are only occasionally useful. In the abyssal depths, the animals swim in ink. Along coasts, the water is so turbid that animals see, at most, a body length ahead. Sound reveals the shapes, energies, boundaries and other inhabitants of the sea. Sound is also a communicative bond. In the ocean, as is true in the rainforest where dense foliage occludes vision, sound connects you to unseen mates, kin and rivals, and it alerts you to nearby prey and predators.

If salmon were abundant, all this noise might not be a problem. But the chinook salmon that compose most of the whales’ diet here are in crisis. Dams, urbanisation, agriculture and logging have cut off or degraded most of the freshwater rivers and streams in which the fish spawn and live out their first months.

Chinook salmon numbers in this region have declined by 60% since the 1980s, and possibly more than 90% since the early 20th century. Under current conditions, models forecast, at best, a fragile southern resident population. Any additional stress will send them to extinction.

A humpback whale and her calf. Photograph: lindsay_imagery/Getty

CONTINUE HERE: https://thefreeonline.com/2022/11/29/blasting-the-ocean-with-noise-how-sonic-pollution-and-sea-mining-will-destroy-marine-life/

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo

Sat Mar 23, 2024 11:33 pm by globalturbo